Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER THREE THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM AND POLICY CONTEXT OF TEACHER APPRAISAL IN BOTSWANA

INTRODUCTION

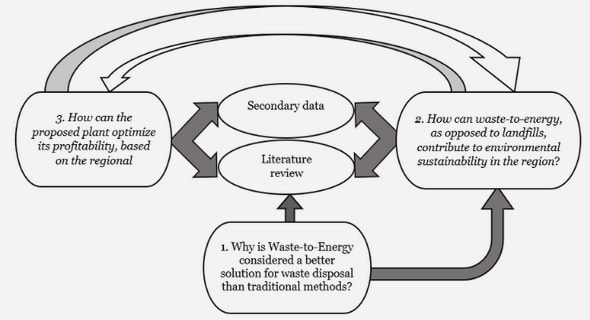

This chapter provides an overview of the educational policy context of this study. Because very little has been published on the Botswana education system, especially with regards to teacher appraisal, the literature review will be based mainly on official documents such as the National Development Plans, reports of National Commissions on Education, circulars from Government Ministries, other policy documents, conference and seminar papers, print media, unpublished dissertations and theses, and the few published books and articles on education in Botswana.

The first part of this chapter briefly reviews educational policy formulation in Botswana since independence from Great Britain in 1966, with particular emphasis on the developments in secondary education, such as teacher demand and supply, the rapid and massive expansion of secondary education system, and how the two impacted on the quality of education offered in the schools. The two aspects of the demand and supply of teachers and the rapid and massive expansion of secondary education are emphasized in relation to their impact on the appraisal process as carried out in Botswana secondary schools.

This chapter then discusses the development of the appraisal process in Botswana secondary schools and how it relates to the context described in Chapter Two. Furthermore, the relevance, strengths and shortcomings of the current appraisal process are discussed in relation to findings from Chapter Two. Some developments in the education system, such as school-based in-service training, parallel progression, and decentralization of some functions of the Ministry of Education are also discussed.

THE DEVELOPMENT OF SECONDARY EDUCATION IN BOTSWANA SINCE INDEPENDENCE

This section briefly describes the development of secondary education in Botswana since independence in order to highlight issues that have a bearing on the rationale for the introduction of teacher appraisal. It also provides background information to accord the reader the opportunity to understand why events unfolded in certain ways. Finally, the information provided in this section gives a context within which teacher appraisal was introduced in the education system as it could not be done in isolation.

According to the Report of the British Economic Survey Mission, the general state of education in Botswana at independence in 1966 was very poor, and this impacted negatively on the manpower requirements, and the economic, social and cultural development of the country (Republic of Botswana 1966:8; Coles 1986:7). This may not be surprising when one considers the aim of education in the context of colonial rule. According to Galetshoge (1993 :76), the aim of the education system during the colonial era was to produce a limited number of the manpower required for the few available positions of employment in the Colonial Government and Tribal Administration as clerks, interpreters, and low-level nursing and teaching staff, jobs that did not require standards above primary education at that time. Education was designed to produce the calibre of personnel efficient enough to cope with the demands of the work prescribed. This attitude of the colonial masters towards the provision of education for the colonised led to the neglect of secondary education in the colony.

Due to the long neglect of secondary education by the colonial administration, there was an acute shortage of local trained manpower in 1966 when Botswana attained independence (Republic ofBotswana 1966:8; Tlou & Campbell 1994:207). For instance, at independence there were only nine secondary schools, with only one Government school, Gaborone Secondary School, which came on stream in 1965. The rest were built by tribal authorities and missionaries (Mautle 1996:104). In 1965, the secondary education system produced only 16 students who were capable of undertaking higher education. The neglect of secondary education also resulted in only forty Batswana holding university degrees in 1966, and only six of these graduates were teachers (Republic of Botswana 1966:34; Mautle 1996:104; Ramorogo, Mapolelo and Mooko 1998:8).

It was therefore not surpnsmg that when Botswana gained its independence in 1966, the new government pledged to give priority to the expansion of secondary education to provide a base for the development of skilled human resources for various sectors of the country’s economy (Mautle 1996:107). According to Leburu-Sianga & Molobe (2000:7), the thinking behind concentrating on the expansion of secondary education was that a crop of secondary school leavers would be trainable and this would allow the country to train for different needs of the economy including training for the education sector. The primary aim in the field of education was to create in the shortest possible time, a stock of trained local manpower capable of servicing the young economy (Republic of Botswana 1966:33; Coles 1986:7; Vanqa 1998:11).

Since independence, the Government of Botswana has approached the provision of education in a systematic way through a combination of highly focused and consistent policies that are in line with National Development Plans (Leburu-Sianga & Molobe 2000:24). The development of the education system of Botswana has been guided by two policy documents, namely, the Report of the National Commission on Education: Education/or Kagisano (Social Harmony) of 1977 and the Revised National Policy on Education of 1994. The two policy documents are briefly discussed below.

The first national commission on education: Education for Kagisano (social harmony) of 1977

By 1975, the education system of Botswana had made some progress in the development of secondary education as the number of schools had increased from nine to 15 with a trained teaching force of 32% (Republic of Botswana 1977a:119). However, the Government felt that although education might have grown much, it had changed little as it failed to respond to fresh demands in terms of attitudes, skills, and abilities (Republic ofBotswana 1977b:l); Molosi 1993:41). There was even a belief among the public that the quality of education had declined as a result of the expansion. This resulted in a widespread feeling that the time had come to take a new look at the provision of education in the country (Republic of Botswana 1977b:l; 1992:3).

In response to the situation described above, and after lengthy consultations, the first President of Botswana, the late Sir Seretse Khama, established a National Commission on Education in December 1975, and its findings and recommendations were adopted by Parliament in 1977. These formed the basis for the Report of the National Commission on Education, Government Paper No. 1 of 1977: Education for Kagisano (Social Harmony) (Molosi 1993:43; Republic of Botswana 1990:2). This policy document was intended to guide the education system of Botswana for the next twenty-five years.

The first National Commission on Education of 1977 proposed among other things reforms which called for the expansion of secondary education in relation to the manpower and social needs and resources available to Government (Republic of Botswana 1985:123; 1991 :325; Motswakae 1990:3). The aim of this expansion was to expand basic education from seven to nine years, as clearly stated in Recommendation 35 (Republic of Botswana 1977b:89):

The Commission recommends that over a long term, Botswana should move toward nine years ofvirtually universal education. The primary cycle should be shortened to six years and should be followed by three years in junior secondary school for all students. Such a system should be feasible by 1990.

As clearly indicated in section 1.2, full implementation of the proposals for the rapid and massive expansion were delayed. However, some projects related to the proposed reforms were carried out, inter alia, the increase in secondary schools as illustrated in table 3.1.

As from 1984, the expansion of secondary education, especially at the junior level, was accelerated to meet the projections proposed in Recommendation 35 of the 1977 Commission on Education. Table 3.2 shows the continuation rates of students from primary to secondary schools in the period 1984 to 1991 (Republic of Botswana 1991a:323)

It can be argued that the first National Commission on Education’s objective of expansion of secondary education in both qualitative and quantitative terms was on track because by 1990 there were 143 junior secondary schools and basic education was at 65 % (Mautle 1996: 109). Furthermore, the curriculum had been diversified to include practical subjects such as Design and Technology, Home Economics, and Agriculture; and the number of qualified local teachers in the teaching force had increased from 101 in 197 6 to about 2 500 in 1991 (Republic of Botswana 1991a:323).

However, the implementation of the reforms proposed by the 1977 Commission brought with it some problems as illustrated in section 3.2.2 below. The Government, with pressure from the public, felt that there was a need to establish another Commission on Education in order to address these problems.

The Revised National Policy on Education of 1994

The former President of the Republic of Botswana, Sir Ketumile Joni Masire, appointed the second National Commission on Education in April 1992. The Commission was basically required to conduct a broad ranging review of the entire education system, with particular emphasis on universal access to basic education, vocational education and training, preparation and orientation towards the world of work, articulation between the different levels of the educational system and re-examination of the education structure (Republic of Botswana 1993:ii). The report of the Commission was adopted by Government as the Revised National Policy on Education, Government Paper No. 2 of 1994. It spelt out the strategy for the educational development whose long-term aim was to take the education system into the 21st Century.

While recognizing the significant quantitative achievements of the first National Commission on Education of 1977, especially in the large number of secondary schools and the relatively high number of students who enrolled in junior secondary schools (see tables 3.1 and 3.2), the Report of the National Commission on Education of 1993 and the subsequent Government White Paper No. 2 of 1994, the Revised National Policy on Education, laments the fact that the massive expansion has placed the system under enormous strain and

» … the result of these developments is that the public is highly critical of the quality of junior secondary education » (Republic of Botswana 1993:ix; 1994b:3). Bartlett (1999:6) contends that one of the aims of the Revised National Commission on Education of 1994 was to instil the element of quality in the education system, a priority pointed out by the commissioners when they declared that:

… the success in quantitative development of the school system has not been adequately matched by qualitative improvements .

. . . quality assurance measures will be a major priority in the overall development of education (Republic of Botswana 1994b:3).

Among some of the objectives of the Revised National Policy on

Education of 1994 were to:

i) raise the educational standards at all levels;

ii) achieve efficiency in educational development;

iii) make further education and training more relevant and available to large numbers of people;

iv) improve the management and administration of schools to ensure higher learning achievement;

v) improve the quality of instruction;

vi) implement broader and balanced curricula geared towards developing qualities and skills needed for the world of work;

vii) return to the three years of junior certificate course; and

viii) embark on measures aimed at raising the status and morale of teachers (Republic of Botswana 1994b:5-11; 1997b:8; 1999: 16-17).

The implementation of these objectives had far-reaching consequences for the whole education system (Republic of Botswana 1997b:8; 1999: 17). Firstly, the expansion of secondary education in order to achieve ten years of basic education which was introduced by the extension of the junior certificate course to three years in 1996 meant that more students with mixed abilities found their way into the school system; a situation which required teachers to adapt their teaching techniques. Secondly, the diversification of the curriculum to include new subjects demanded more teachers and new techniques to classroom approaches. Thirdly, the expansion did not only strain the economic and administrative structures, but also placed a lot of pressure on the teachers themselves, a situation which needed attention as it could lead to demotivation and less productivity. Fourthly, the achievement of 100% enrolment in basic education resulted in a heightened demand for senior secondary spaces.

Much as the Government of Botswana was committed to a systematic approach to education and spent a sizable amount of the country’s financial resources in education, it should be realized that one of the main factors in the attainment of quality education is the calibre of the teachers who play a pivotal role in driving the education system. The supply of qualified teachers has been on the development agenda of the Government of Botswana, a point emphasized by Kedikilwe (1998:8) when quoting a UNESCO official who once said » …

education for all cannot be achieved or even approached without the commitment of teachers to search for and find education within the reach of all ». Teachers are, therefore, a very important cog in the wheel of quality provision of education, and this is discussed in the next section.

Teacher training and supply

It has been observed that over the past two decades, teachers and teaching have received a fair amount of attention from education policy makers, funding agencies, and educational quality improvement researchers in developing countries, and in Africa in particular (Marope 1997 :3 ). Governments’ interest in education is not peculiar to developing countries alone as illustrated in section 2.8, whereby political intervention in matters of education in Great Britain and the United States of America was highlighted.

Marope (1997:3) identifies three main reasons why governments and other stakeholders the world over have developed such interest in education, particularly in teachers and teaching. Firstly, teachers are the most significant instrument for effecting student learning and this role is even perceived to be higher in developing countries where the culture of the school and that of the home are mostly at variance. The situation is further exacerbated by such hardships as the acute shortage of curriculum and instructional materials, and poor professional support materials.

Secondly, teachers remam the most significant implementers of interventions and reforms intended to improve the quality of education and ultimately student learning. They are, therefore, the gatekeepers between policy reforms, interventions, and students’ actual learning experiences. Thirdly, as one of the largest cadres of the civil service, and due to the proportionate expenditure involved, it is proper for the stakeholders to question whether the observed quality of teaching warrants the expenditure on teachers. As in the two case studies of Great Britain and the United States of America in section 2.8, the interest is mainly to make teachers accountable. This point is succinctly made by Kedikilwe (1998:8) referring to the situation in Botswana: « . . . much as government continues to support the education sector with the necessary resources, including trained and experienced teachers, it is not evident that there is a commensurate increase in the quality of the product at school level ».

Since Botswana attained independence, the Government recognized the vital role that can be played by teachers in the ultimate goal of students learning; but was concerned with the calibre and supply of teachers. Khan (1997:237) vehemently argues that one of the main concerns of the first Commission on Education of 1977 was the teachers’ low level of qualifications. The shortage of qualified teachers was made worse by the rapid and massive expansion of secondary education which forced the Government to increase the proportion of untrained teachers and recruit more expatriate staff (Republic of Botswana l 997b: 18). One of the main disadvantages of the untrained teachers is that they are not equipped with the necessary skills and knowledge to effectively handle the teaching and students’ learning processes; while many of the expatriate teachers came from countries with different education systems and had to adapt to the system of Botswana. It was also discovered that many expatriate teachers were not trained to teach (Dadey & Harber 1991:6; Republic of Botswana 1997a: 119; Vanqa 1998:172-3).

In an attempt to solve these problems, the Government of Botswana decided to expand the training programme through two strategies: the expansion of the University; and the opening of two Colleges of Education to train teachers for junior secondary schools only. Unfortunately, the local institutions could not cope with the demands for qualified teachers as the education system continued to expand and this forced the Government to continue with the recruitment of expatriates and untrained teachers. The supply of teachers also suffered from other factors which militated against effectiveness and efficiency. Firstly, it is not easy to conceptualise and plan a relevant curriculum to cater for the broad range of student abilities and aptitudes found in the rapidly expanding educational system (Rathedi 1993 :97). Secondly, the conditions of service in the teaching profession do not attract academically high performers who would be committed to the job of teaching. Thirdly, due to the high demands of teachers caused by the expansion and diversification of the curriculum, entry requirements into the colleges of education were lowered.

The background information has illustrated that secondary education in Botswana has been undergoing a lot of transformation which can impact negatively on the twin processes of teaching and student learning in the schools if stabilizing strategies are not put in place. In order to address the teaching and learning process, one of the strategies adopted was the introduction of teacher appraisal. The next section discusses the introduction of teacher appraisal in Botswana secondary schools, which is the main focus of this study.

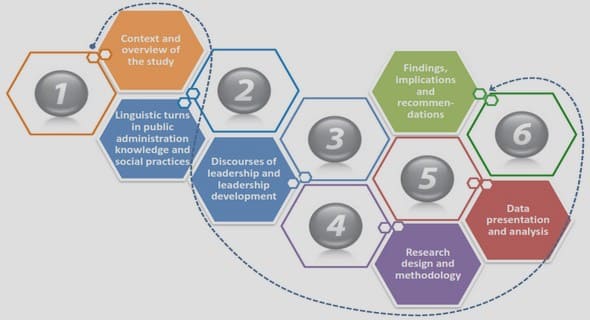

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CHAPTER ONE ORIENTATION OF THE STUDY

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Brief history of education in Botswana

1.3 Appraisal in Botswana secondary schools

1.4 Significance of the study

1.5 Problem statement

1.6 Objectives of the study

1. 7 Research methods and design

1.8 Definition of terms

1.9 Organization of the study

1.10 Summary

CHAPTER TWO LITERATURE REVIEW: TEACHER APPRAISAL

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Performance appraisal

2.3 Purpose of appraisal

2.4 Teacher appraisal

2.5 Advantages and disadvantages of appraisal

2.6 Models of appraisal

2.7 The appraisal process

2.8 History of teacher appraisal in Great Britain and the United States of America

2.9 Conclusion

CHAPTER THREE THE EDUCATIONAL SYSTEM AND POLICY CONTEXT OF TEACHER APPRAISAL IN BOTSWANA

3 .1 Introduction

3 .2 The development of secondary education in Botswana since independence

3.3 Teacher appraisal in Botswana secondary schools

3.4 Summary

CHAPTER FOUR RESEARCH DESIGN

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Restatement of the research question

4.3 Aims and objectives of the study

4.4 Research methods

4.5 Data collection techniques

4.6 Population and sampling procedures

4.7 Data analysis

4. 8 Trustworthiness of the research

4.9 Summary

CHAPTER FIVE RESEARCH FINDINGS: ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSIONS

5.1 Introduction

5 .2 Demographic data

5 .3 Analysis and discussion of research findings

CHAPTER SIX SUMMARY, CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Summary

6.3 Conclusions

6.4 Recommendations

6.5 Recommendations for further research

6.6 Concluding remark

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT