Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Frame of Reference

In the frame of reference chapter, the authors discuss the selected academic theories and models that are important and relevant to the thesis. The frame of reference has been divided into seven parts. The first part discusses the definition and framework of CSR. The second part argues logistics service providers (LSPs) including activities and functions that LSPs offered. The next part discussed the definition of a TPL provider as well as the criteria when choosing TPL providers. CSR in logistics providers and driving forces for adopting CSR are showed. Finally, the research framework of this study and summary of the frame of reference chapter are presented

CSR and its definition

Corporate social responsibility (CSR) is a broad concept and can be defined in various ways. Carroll (1999) pointed out before CSR became well known; it was common to refer to social responsibility (SR) instead of CSR. It might be because the period of the modern corporation’s distinction and power in the business area had not yet appeared or been written. Perhaps, Bowen (1953) wrote the first definition of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) “it refers to the obligations of businessmen to pursue those policies, to make those decisions, or to follow those lines of action which are desirable in terms of the objectives and values of our society (p.6).” Davis (1960) argued the definition of social responsibility refers to “businessmen’s decisions and actions taken for reasons at least partially beyond the firm’s direct economic or technical interest (p.70).” He also argued that there are two faces for social responsibility. The first is that businesses recognize themselves – since they manage an economic unit in community, they should have a broad obligation to the society regarding an economic development affecting the public benefit. The second face is businesses’ obligation to support and develop human value such as morale in work

The CSR framework

Corporate Sustainability1 is another well-known perception to discuss an organization’s responsibility beyond legal commitment (Blombäck, Wigren-Kristoferson & Florin-Samuelsson, 2010). CS can be seen as the aim with CSR as a transitional stage where organizations try to maintain balance with the Triple Bottom Line. However, in practice CSR and corporate sustainability is defined as a synonym (Marrewijk, 2003).

Figure 2.1 CS, CSR and 3Ps. (Wempe & Kaptein, cited in Marrewjik, 2003, p.101)

CSR is sometimes referred to as the triple bottom line (TBL): profit, people, and planet (see figure 2.1) (Marrewijk, 2003) or it can be the criteria for measuring organizational success beyond the legal obligations: in content of economic, social and environmental (Commission of the European Communities, 2002). The three areas as showed also present the responsibility to operate in ways that correspond to expectations that appear where organizations operate (Blombäck et al., 2010). In addition, it may also have an impact on the firm’s reputation and image, which may also have a significant economic impact to company (Commission of the European Communities, 2002).

The first domain is economic: the businesses should be profitable in the process, but in some points the profit motive turned into an idea of maximum profit instead. Economic responsibility can be seen as the foundation of businesses since Carroll (1991) stated that « all other business responsibilities are predicated upon the economic responsibility of the firm, because without it the others become moot consideration » (p.41). Moreover, Blombäck et al. (2010) argued that the economical domain refers to the fact that businesses act in order to reach the demands of customers in the market and to run companies at a profit.

In terms of planet or environmental or ecology issues, Halldorsson et al. (2009) argued that the environmental aspect has had the main impact on sustainable growth. Dyllick and Hockerts (2002) defined ecologically sustainable companies as “companies use only natural resources that are consumed at a rate below the natural reproduction, or at a rate below the development of substitutes. They do not cause emissions that accumulate in the environment at a rate beyond the capacity of the natural system to absorb and assimilate these emissions. Finally they do not engage in activity that degrades eco-system services” (p.133). Examples of potential environmental risks are potentially polluting emissions, environmental hazards and risk, and consumption of critical natural capital (Mitchell, 1998).

Halldorsson et al. (2009) pointed out that the best way to describe a company’s social responsibility is people. Hutchins and Sutherland (2008) proposed four social performances that businesses should establish. Firstly, labor equity expresses the distribution of worker compensation within a company. Secondly, health care is needed to characterize a corporation’s role in providing or helping the health care of companies’ staff as well as their families. Safety refers to the safety of the workplace within a company. Lastly, philanthropy describes financial support that companies offer to community and to greater community. Activities like these do not concern to its core tasks as a business, such as building museums and providing scholarship to students.

However, there is another famous CSR framework, namely the pyramid of CSR. Carroll (1991) suggested that the CSR framework, divided into four kinds of social responsibilities would constitute: economic responsibilities, legal responsibilities, ethical responsibilities, and philanthropic responsibilities (see figure 2.2). Economic responsibilities require businesses to produce goods and services, which are needed in society. Legal responsibilities require that businesses perform under the laws and regulations promulgated by the nation, state or even local governments. These responsibilities also reflect a view of ethical responsibilities in the next layer. Ethical responsibilities correspond with norms or expectations, which concern for what stakeholders regard as the moral right and it is beyond the law and regulations such as environmental concern. Finally, philanthropic responsibilities refer businesses to be a good corporate citizen. Examples of philanthropy are donations of a financial resource or time to charity and it is more voluntary as the icing on the cake.

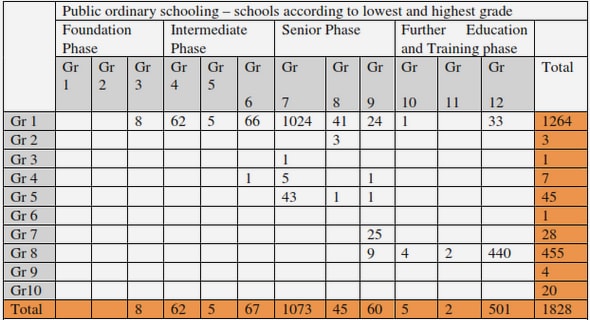

In the study “Corporate Social Responsibility: A Review of the Top 100 US Retailers” by Lee et al. (2009), they proposed the examples of each CSR dimension from Carroll’s CSR pyramid (see table 2.1). Based on that study and the Triple Bottom Line CSR framework, the authors present examples of CSR statements in table 2.2

Logistics service providers (LSPs)

There are three groups of Logistics service providers (LSPs), which are sub-contract carriers, logistics service providers (TPL providers), and logistics service intermediaries (freight forwarder) (Cui & Hertz, 2011). There are differences among these three types as such as firm’s core competence and network development. Even so, they are each other’s suppliers and customers at the same time (Cui & Hertz, 2011). Table 2.3 presents each type of LSPs capabilities in operating network system and in managing network of physical flows in table 2.4.

Sub-contract carriers: Carriers provide physical transport of material from point A to point B (Cui & Hertz, 2011). Examples of services provided by the carriers were door-to-door transportation service, inbound and outbound transportation, and contract delivery (Stefansson, 2006).

Logistics service providers (TPL providers): TPL providers can be either non-asset based or asset based. Asset based third party logistics companies provide physical service primarily through the use of their own property, such as warehousing and IT systems. Non-asset based third party logistics companies provide their knowledge and expertise, often leading them to being called knowledge based logistics service providers and lead logistics providers (Cui & Hertz, 2011). Typical services of TPL providers concern at least management and administration of warehousing or transport. Other service activities can also include, for instance inventory management, value-added activities i.e. secondary assembly of goods, information related service i.e. tracking, or even management of the supply chain (Laarhoven et al., 2000). However, the most common services of TPL are transport, warehousing, inventory (Hertz & Alfredsson, 2003).

Logistics service intermediaries: These are often non-asset based service providers and their tasks concern the coordination and connection of different logistics actors and their activities (Cui & Hertz, 2011). They do not handle the goods personally but work with administrating the different logistics activities (Stefansson, 2006). Logistics intermediary companies frequently deal with freight forwarding activities, such as the consolidation of physical products. The diversity of logistics intermediaries in the market can be divided into freight forwarder, consolidator, broker, and other types (Cui & Hertz, 2011)

A ctivities of logistics service providers (LSPs)

Logistics service providers have grown in importance, as can be seen from the increasing demand (Delfmann, Albers & Gehring, 2002). According to Jharkharia and Shankar (2005), the trend of logistics outsourcing is growing and many logistics service providers are now providing a variety of services. Table 2.5 presents various services that LSPs offered to customer.

What is a TPL provider?

Before discussing the criteria when selecting TPL providers, the meaning of the term TPL provider should be discussed. The definition of a TPL provider is difficult to uniform or standardize (Knemeyer & Murphy, 2005). Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) define TPL provider as “an external provider who manages, controls and delivers logistics activities on behalf of a shipper (p.140).” The first party is the shipper or supplier, the buyer is the second party, and the third party is a firm. The firm acts in between two parties for those specific logistics activities but the firm does not have ownership of the goods. However, the terms outsourcing and contract logistics occasionally replace TPL providers, depending on the firms’ type and the industry’s positioning (Langley, Coyle, Gibson, Novack & Bardi, 2008). The TPL provider market is growing continuously. For instance, the growth in the US market has risen from $30.8 billion to $103.5 billion from 1996 to 2005. Nevertheless, table 2.6 shows that European countries have been dominating the global TPL industry (Langley et al., 2008).

The Classification of TPLs providers

Hertz and Alfredsson (2003) classified TPL providers into four subgroups: TPL provider, service developer, customer adapter, and customer developer. These were based on two dimensions, namely customer adaptation and general ability for problem solving. Each subgroup had different demands on problem solution ability and customer coordination and adaptation (see figure 3).

The first type is called a standard TPL provider, which supplies the standardized TPL services like distribution, warehousing as well as pick and pack. The second is a service developer that offers advanced value-added services. This type of TPL provider focuses more on creating economies of scale and scope as well as IT systems, often involving an advanced service package. Forming specific packaging, cross-docking, track and trace and offering special security systems are examples of services. The TPL as customer adapter has a high customer adaptation, but does not conduct much development of services. It is seen as taking over customers’ existing activities, such as total warehouse activities, and depends on a few very close clients. The last type is the most advanced and difficult form, named customer developer. Frequently, it engages in a high integration with customers in the form of taking over the entire logistics operations. The TPL as customer developer more plays the role of a consultant. Therefore, the possibilities to synchronize customers rather lie in the knowledge improvement, the know-how, and the design of the whole supply chain (Hertz & Alfredsson, 2003)

1.Introduction

1.1.Background

1.2.Problem statement

1.3.Purpose

1.4.Research questions

1.5.Delimitation

1.6.Thesis outline

2.F rame of Reference

2.1.CSR and its definition

2.2.Logistics service providers (LSPs)

2.3.What is a TPL provider?

2.4.Criteria when selecting TPL providers

2.5.CSR in logistics providers

2.6.Driving forces for adopting CSR

2.7. Research F ramewor k of this study

2.8.Summary of F rame of Reference

3. Methodology

3.1.Research approach

3.2.Research design

3.3.Quantitative method

3.4.Qualitative method

3.5.Data collection

3.6.Selecting samples

3.7.Analysis of the empirical data

3.8.T rustworthiness of the research

3.9.Ethical concerns

3.10.Summary of Methodology chapter

4.Empirical research

4.1.Company Background

4.2.Driving forces of CSR

4.3.Selection criteria when buying services from TPL providers

4.4.CSR Practice in TPL providers

4.5.Summary of empirical materials

5.Analysis

5.1.Driving forces of CSR

5.2.Selection criteria when buying services from TPL

5.3.CSR Practice in TPL providers

5.4.Summary of Analysis

6.Conclusion

6.1.Summary

6.2.Limitation of Study

6.3.Future research

7.References

8.Appendixes .

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT