Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 2 CURRICULUM THEORY, CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT AND CURRICULUM IMPLEMENTATION

INTRODUCTION

It is normal to discuss curriculum matters, and especially curriculum implementation, without considering the complexities concerned. In Mozambique, for instance, it is widely held that students‘ poor academic performance is caused by shortcomings in the curriculum when the fault should in fact be sought in the teaching-learning process, which is merely a part of curriculum. Macdonald (2006:4) observes that ―…a lot of attention is paid to the outcomes or results of our activities in terms of student results, less energy is expended in finding out how well we carry them out‖. As Hameyer (2003) noted, the quality of a curriculum can only be as good as the quality of the curriculum process, depending on the self-renewing capacity of the individual school. Likewise, Lovat and Smith (2003:74) emphasize that ―student achievement can only be enhanced when the nature of the pedagogy required is targeted with precision and implemented with rigour, and with assessment for outcomes that is in tune with the entire process.‖ Therefore, Glatthorn, Boschee and Whitehead (2006:73) point out that it ―is essential to develop a fundamental understanding of curriculum theory by the providing the tools necessary when analyzing curriculum proposals, illuminating practice, and guiding reform.‖

In effect, three distinct levels, perspectives or representations, namely, ―intended‖, ―implemented‖ and ―attained‖ curriculum are often confused in a way that it is easily and superficially concluded from the outset of the initiative that the curriculum change, which is innovation, is doomed to failure. As Lovat and Smith (2003:133) point out, ―the truth is that good curriculum is theory-and-development, planning and practice, as one. When we opt for one against the other, we do damage to good learning.‖ Indeed, it is essential for a critical analysis of curriculum implementation to proceed with due deference to this observation.

It follows, therefore, that all curriculum approaches (e.g. behavioural, managerial, systems, academic, humanistic and reconceptualists) must be given their due in overall curriculum development, and curriculum theory must guide all curriculum activities (Zais, 1976; Marsh, 2004). In light of the above, this chapter is intended to raise awareness of the curriculum in concept and the perspectives and approaches that serve as criteria for curriculum evaluation, with particular reference to curriculum theory and curriculum development.

Thus, accurate analysis and understanding of curriculum implementation is made possible by taking due account of the curriculum concept, the perspectives on and approaches to school curriculum, and curriculum theory and development. That is, before we deal with issues about curriculum implementation in Mozambique, it is worth addressing questions about the purpose and nature of curriculum. Incidentally, Ornstein and Hunkins (1993:184) aver that theoretical perspectives may allow us ―to bring to bear our repertoire of habits, and even more important, to modify habits or discard them altogether, replacing new ones as the situation demands‖. Therefore, the purpose of this chapter is to provide a theoretical background in order to shed light on the nature of the new basic education curriculum in Mozambique and the means required for its successful implementation, to be considered in detail in chapter 3.

So, based on theoretical background incorporated into chapter two, compared with the new curriculum development approach of basic education in Mozambique presented in chapter three, the findings reported in chapter five are critically analysed and discussed in chapter six. Finally, the conclusions, recommendations and implications covered by chapter seven are substantiated.

It will be seen from the discussion of theoretical background that as Posner (2004:4) asserts, ―there is no panacea in education and it is reflective eclecticism that is at the heart of curriculum study.‖ In the same vein, Doll Jr (2002:45) avers that curriculum is currently understood as ―a process or method of ‗negotiating passages‘- between ourselves and the text3, between ourselves and the students, and among all three.‖ It is hoped that the background discussed here will serve as adequate preparation for a critical appraisal of the process of implementing the new basic education curriculum in Mozambique.

THE CURRICULUM CONCEPT

According to Smith (1996, 2000:1) ―the idea of curriculum is hardly new – but the way we understand and theorize it has altered over the years — and there remains considerable dispute as to meaning‖. Therefore, defining the word curriculum is no easy matter (Marsh & Willis, 2003:7). It consists of disjunct or fragmentary parts. Ornstein and Hunkins (1993:1) aptly note that ―curriculum as a field of study is elusive and fragmentary, and what it is supposed to entail is open to a good deal of debate and even misunderstanding.‖ Lovat and Smith (2003:6) confirm that:

The word (curriculum) itself is used in many different contexts, by principals in schools, by teachers, by curriculum writers in education systems, and increasingly by politicians. It can mean different things in each of these contexts.

In fact, definitions of curriculum abound in the literature, in various autonomous discourses using key terms in complex and even in contradictory ways (Pinar et al., 1995). The core meaning of curriculum is embodied in its Latin derivation from a ―course‖ or ―track to be followed‖. Marsh and Stafford (1988:2) confirm that ―the word curriculum comes from the Latin root meaning ―racecourse‖ and, for many, the school curriculum is just that — a race to be run, a series of obstacles or hurdles (subjects) to be passed.‖ Marsh and Stafford (1988) highlight three dimensions of curriculum concept. First, they explicit that curriculum includes not only syllabi or listing of contents, but also a detailed analysis of other elements such as aims and objectives, learning experiences and evaluation as well as recommendations for interrelating them for optimal effect. Second, ―curriculum‖ comprises planned or intended learning, calling attention to unexpected situations which necessarily may occur in the classroom practices. Third, curriculum and instruction are inextricable. Lovat and Smith (2003:16) rightly contend that ―curriculum is part of teaching, not separate from it.‖ Therefore, the most agreed basic notion of the curriculum is that it refers to a plan for learning (Todd 1965; Neagley & Evans, 1967; Zais 1976, Marsh & Stafford, 1988; Van den Akker, Kuiper & Hameyer, 2003 and Lovat & Smith, 2003). This concept of curriculum as (cf.Van den Akker 2003:2) ―limits itself to the core of all definitions, permitting all sorts of elaborations for specific educational levels, contexts, and representations.‖ Discussing this curriculum concept, Marsh and Stafford (1988:4) argue that curriculum is an interrelated set of plans and experiences which a student completes under the guidance of the school.‖

Furthermore, Marsh and Stafford (1988:4-5) clarify the comprehensiveness of this definition as follows:

- The phrase, ―interrelated set of plans and experiences‖ refers to the point that curricula which are implemented in schools are typically planned in advance but, almost inevitably, unplanned activities also occur.

- The phrase ―which a student completes under the guidance of the school‖ is included to emphasise the time element of every curriculum.

- ―Under the guidance of the school‖ refers to all persons associated with the school who might have had some input into planning a curriculum and might normally include teachers, school councils and external specialists such advisory teachers.

Strikingly, in line with this curriculum concept, an encapsulated definition was given earlier by Richmond (1971:87), who stated that ―curriculum is a ‗slippery‘ word, meaning in the broadest sense the ‗educative process as a whole‘ and, in the narrowest sense, ‗synonymous with the syllabus, a scheme of work, or simple subjects.‖

However, as Lovat and Smith (2003) point out, the main concern is not to arrive at a specific definition of ‗curriculum‘; rather it is to be aware that:

- Curriculum means different things to different people; it is therefore important to consider the context in which the term is used.

- The meaning attributed to the word ‗curriculum‘ is associated with particular ideology or set of beliefs about education and the world.

- A number of issues and concerns that are central to the nature of curriculum work itself are suggested by different usages and meanings of the term ‘curriculum‘.

Thus, curriculum may be looked at from different perspectives and approaches, which should be clarified if the process of curriculum change is to be understood. According to Van den Akker (2003), a basic analysis concerning curriculum improvement comprises three distinct levels, perspectives or representations, namely: ―intended‖, ―implemented‖ and ―attained‖ curriculum.

In fact, the three salient characteristics of curriculum as stated tend to be modulated by perspective. Nevertheless, they are intrinsically connected to the extent that curriculum implementation cannot be considered without account of the ―intended‖ as well as the ―attained‖ curriculum. I realize that the said three aspects of curriculum constitute a chain with strong links that cannot be ignored in a critical appraisal of curriculum change; hence it is deemed necessary to revisit them to clarify the purpose and direction of the research in hand.

The intended or planned curriculum comprises the ideal or abstractly conceptual curriculum and the formal or written curriculum (Goodlad 1979; Saylor, Alexander & Lewis 1981; Marsh & Willis 1999; Hameyer 2003). The ideal curriculum is the vision, including information that presents an overview (bird‘s–eye view) of ―why‖, ―when‖, ―how‖ and ―what‖ is supposed to be taught and learned. It is the rationale, the basic philosophy or the epistemological base underpinning the curriculum. The formal, written curriculum covers the practicalities of ―why‖, ―when‖, ―how‖ and what‖ as expressed, for example, in curriculum documents, syllabi, or in school resources such as textbooks and other materials. Posner (2004) refers to it as the official curriculum. How curriculum is implemented depends on users‘ perceptions and, therefore, how they are influenced by the implementation, which is the actual process of teaching and learning (the enacted curriculum — Marsh & Willis 1999; the operational curriculum — Hameyer 2003; the observed curriculum — Saylor, Alexander and Lewis 1981). It is the real curriculum, the curriculum-in-action

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION AND GENERAL ORIENTATION: PROBLEM STATEMENT, RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND AIM OF THE INVESTIGATION

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Historical background

1.3 Problem statement

1.4 Research questions

1.5 Aims and objectives of the investigation

1.6 Theoretical framework

1.6.1 Regarding clarity among members about and identification with new goals and role expectations factor

1.6.2 Concerning members’ ability to fulfil the new role expectations

1.6.3 Regarding the presence of adequate resources

1.6.4 About a compatible organizational or social envelope for innovation (See figure 1.1)

1.6.5 On the planned process of role resocialization

1.6.6 Concerning considerable time, coordination, support, and encouragement

1.6.7 Regarding school leadership

1.7 Research methodology applied during the investigation

1.8 Clarification of terms and concepts

1.9 Outline of research and timeframe

1.10 Summary

CHAPTER 2 CURRICULUM THEORY, CURRICULUM DEVELOPMENT AND CURRICULUM IMPLEMENTATION

2.1 Introduction

2.2 The curriculum concept

2.3 Curriculum approaches

2.3.1 The behavioural approach

2.3.2 The managerial approach

2.3.3 The systems approach

2.3.4 The academic approach

2.3.5 The humanistic approach

2.3.6 The reconceptualists

2.3.7 Summary: Brief comment on curriculum approaches

2.4 The nature and functions of curriculum theory

2.4.1 Introduction

2.4.2 The nature of curriculum theory: categories of knowledge

2.4.3 The functions of curriculum theory with specific reference to description, prediction, explanation and guidance in the process of school curriculum development

2.5 Curriculum development: planning or designing, dissemination, implementation and evaluation

2.5.1 Clarifying the concept

2.5.2 Components and phases of curriculum development

2.5.2.1 Introduction

2.5.2.2 Curriculum design

2.5.2.3 Curriculum dissemination nationwide

2.5.2.4 Curriculum implementation: Curriculum context and factors influencing curriculum implementation

2.5.2.5 Curriculum evaluation

2.5.3 The curriculum development models

2.5.3.1 The Taba model

2.5.3.2 The Saylor, Alexander, and Lewis model

2.5.3.3 The Tyler model

2.5.4 Summary: some personal remarks on curriculum models

CHAPTER 3 THE STRUCTURE, NATURE AND INTRODUCTION OF THE NEW BASIC EDUCATION CURRICULUM (BEC) IN MOZAMBIQUE

3.1 Introduction

3.2 The structure of the new curriculum

3.3 Policy that informs and innovations subsumed by the new curriculum

3.4 Curriculum implementation strategies

3.5 Nationwide implementation of new Curriculum

3.6 Conclusion

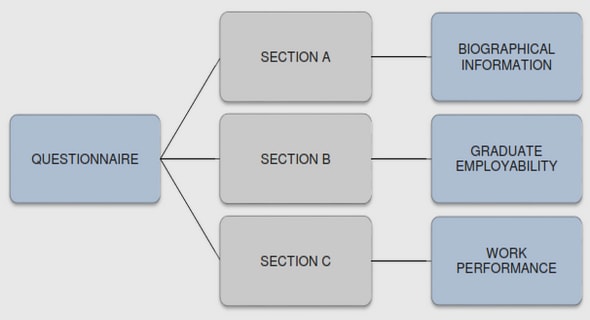

CHAPTER 4 RESEARCH STRATEGIES AND TECHNIQUES APPLIED DURING THE INVESTIGATION

4.1 Introduction

4.2 Justification of the use of a quantitative research strategy during the course of the investigation

4.3 The content validation of the questionnaire

4.4 Statistical techniques and calculations applied during the investigation

4.5 Application of the questionnaire and time frame

4.6 Reliability and Validity

4.7 Summary

CHAPTER 5 REPORTING AND ANALYSES OF THE EMPIRICAL DATA

5.1 Introduction

5.2 Results of the quantitative analysis of principals’ questionnaires

5.3 Results of the quantitative analysis of teachers’ questionnaires

5.4 Results of students’ questionnaires

5.5 Introduction

5.6 Results of the first-order investigative factor analysis

5.7 Results of second-order confirmative factor analysis

5.8 Summary

CHAPTER 6 ANALYSIS AND DISCUSSION OF THE RESULTS

6.1 Introduction

6.2 Discussion of results of the quantitative analysis of principals’ questionnaires

6.3 Discussion of results of the quantitative analysis of teachers’ questionnaires

6.4 Discussion of results of the quantitative analysis of students’ questionnaires

6.5 Discussion of results analyzing principals’ responses

6.6 Discussion of the results of factor analysis of teachers’ responses

6.7 Discussion of the results of factor analysis of students’ responses

6.8 Alignment of results of the frequency analyses with results of the factor analyses (commonalities)

6.9 Summary

CHAPTER 7 THE MAIN FINDINGS, CONCLUSIONS, RECOMMENDATIONS AND IMPLICATIONS

7.1 Introduction

7.2 The main problem, research questions, aims and objectives of the investigatio

7.3 Conclusions drawn from the main findings of the investigation

7.4 Reflections on the findings

7.5 Limitations of the study

7.6 Recommendations

7.7 Implications

7.8 Summary.

BIBLIOGRAPHY .

APPENDICES