Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

INTRODUCTION

The global population has passed the six billion people mark and is rapidly increasing towards seven billion (Cunningham, 2001:201). In order to satisfy global needs, the different nations of the world have become interdependent (Smit, 1993:162), necessitating communication between people from diverse backgrounds. Although technology, in particular the internet, has increased, if not maximised, global communication possibilities, it has not diminished the need for language competency. Languages still have a key role to play in harmonising contact between culturally and linguistically diverse individuals. Education, communication, and languages have in fact never been more important, despite the explosion of knowledge in science, medicine, and technology (Genesee & Cloud, 1998:62). Education is no longer merely a priority for educators and parents or caregivers, but business leaders increasingly recognise the connection between global competitiveness and education. Economic forces exercise considerable influence on decision-making in education, in particular language decision-making. Many economists concede that language competence in more than one language has become imperative because of the integral place of language competency in the global market-place (Cunningham, 2001:218; Gumbo, 2001:240; Genesee & Cloud, 1998:62).

THE GLOBAL AND LOCAL CHALLENGES OF MULTILINGUALISM

As a result of major developments in social, economic, and political sectors (Smit, 1993:160), societies all over the world have become linguistically and culturally diverse, with homogeneous societies being the exception rather than the rule. Worldwide, policy-makers have been faced with the challenge of dealing with diversity and have had to adapt in an effort to cope with a variety of languages, religions, ethnic groups, and socio-economic backgrounds, as well as a variety of political views within their boundaries (Genesee & Cloud, 1998:62).

In the United States of America (USA), multiculturalism grew dramatically during the 1980s and numerous sources noted the increase in numbers of the non-English-speaking population (Gumbo, 2001:235; Genesee & Cloud, 1998:62; Montgomery & Herer, 1994:130; Roseberry-McKibbin & Eicholtz, 1994:156; Waggoner, 1993:1). The linguistically diverse population resulted in an increase in the number of learners with limited English proficiency, placing demands on schools to meet the needs of these learners (Garcia & Stein, 1997:141). When illiteracy and limitations in vocabulary, reading, and writing skills increased and high school drop-out rates escalated in the nineties, the education of non-English learners in the USA was placed high on the education agenda (Garcia & Stein, 1997:142; Cheng, 1996:349; Montgomery & Herer, 1994:131-134).

THE SOUTH AFRICAN URBAN PRESCHOOL CONTEXT

It is currently often the case in South African communities that many young learners are placed in English preschools without any prior knowledge of English. Life for these learners entering a new preschool environment may be complicated as they are obliged to communicate and learn in an unfamiliar language while being isolated from their communities and culture (NAEYC, 1996:5). Furthermore, teachers have observed that the behaviour of these learners often affects class activities and discipline. Some learners may appear to be fluent in English, but are unable to understand and express themselves as competently as their English-speaking peers (NAEYC 1996:8; Lemmer, 1995:89). These multilingual preschoolers need to be managed appropriately to develop adequate English language skills, not only for communication but also for learning.

STATEMENT OF PROBLEM AND RATIONALE

Over the past decade parents or caregivers have increasingly enrolled Black learners in South African urban preschools where English is the only MoI in the school. The abrupt change from L1 to English instruction has created a challenging environment for both learner and teacher. From discussions the researcher had with preschool teachers in the Pretoria CBD and Sunnyside area during workshops, it became obvious that several preschools were struggling to prepare multilingual preschoolers for formal schooling in English. The learners’ language deficiencies were reported as being a major obstacle to school readiness. The preschool teachers expressed feelings of frustration because they could not complete their daily educational programmes and they University of Pretoria etd – Du Plessis, S (2006) 18 were also concerned about the multilingual learners’ academic performances and future.

The teachers requested advice and support to respond effectively to the language needs of the multilingual preschool learners, and specifically requested intervention guidelines for the initial stages of the multilingual learners’ acquisition of ELoLT. From these conversations, it was evident that the multilingual preschoolers acquiring ELoLT experienced difficulties on three levels: vocabulary (both receptive and expressive), syntactic structures, and communicative skills (especially pragmatic skills). It was in this unexplored multilingual context that a need was identified for speech-language therapists to make their expertise available to the multilingual preschool learners as well as to their preschool teachers. The current research was initiated in response to these needs of this specific community.

Preschool learner and preschooler

In South Africa children may be placed in ECE centres from infancy. ECE centres or preschools may accommodate infants up to the age of three or, alternatively, children between the ages of three and six years. Both these age groups may also be accommodated in one centre, but different programmes are followed with each age group. Legally learners have to enter primary school the year in which they turn seven, setting the age limit for preschool learners at six years. The term preschool learner or preschooler thus refers to a young child between the ages of three and six years, attending a preschool centre.

TABLE OF CONTENTS :

- LIST OF TABLES

- LIST OF FIGURES

- LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- ABSTRACT

- OPSOMMING

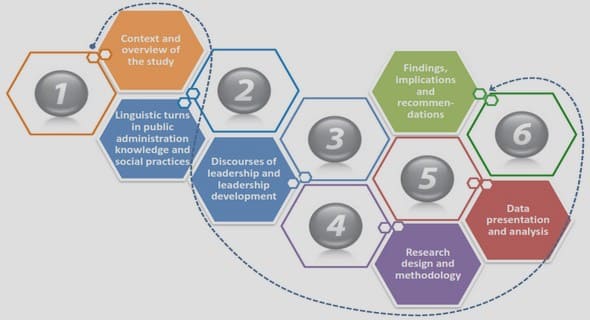

- CHAPTER 1: PROBLEM STATEMENT AND RATIONALE FOR THE STUDY

- 1.1 INTRODUCTION

- 1.2 THE GLOBAL AND LOCAL CHALLENGES OF MULTILINGUALISM

- 1.3 THE ROLE OF SPEECH-LANGUAGE THERAPISTS IN THE ACQUISITION OF ENGLISH AS LANGUAGE OF LEARNING AND TEACHING IN SOUTH AFRICA

- 1.4 THE SOUTH AFRICAN URBAN PRESCHOOL CONTEXT

- 1.5 STATEMENT OF PROBLEM AND RATIONALE

- 1.6 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

- 1.7 DEFINITION OF TERMS

- 1.8 LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

- 1.9 ORGANISATION OF THE STUDY

- 1.10 CONCLUSION

- 1.11 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 2: THE ACQUISITION OF ENGLISH AS LANGUAGE OF LEARNING AND TEACHING:

- THE SOUTH AFRICAN CONTEXT

- 2.1 INTRODUCTION

- 2.2 ENGLISH AS PREFERRED LANGUAGE OF LEARNING AND TEACHING BY THE SOUTH AFRICAN POPULATION

- 2.3 THE LANGUAGE ACQUISITION PROCESS

- 2.3.1 The acquisition of ELoLT

- 2.3.2 Additive multilingualism

- 2.3.3 Subtractive multilingualism

- 2.3.4 Code-switching as teaching strategy in additional language (L2) acquisition

- 2.3.5 Linguistic aspects of additional language acquisition

- 2.4 INFLUENCES ON ELoLT ACQUISITION IN SOUTH AFRICAN LEARNERS

- 2.4.1 Individual influences

- 2.4.2 External influences

- 2.5 CONCLUSION

- 2.6 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 3: MULTILINGUAL LEARNERS IN THE SOUTH AFRICAN SCHOOL CONTEXT

- 3.1 INTRODUCTION

- 3.2 THE IMPORTANCE OF LANGUAGE DEVELOPMENT FOR LEARNING

- 3.3 LANGUAGE DEMANDS OF THE CURRICULUM IN THE EARLY ACADEMIC PHASES

- 3.3.1 The preschool curriculum

- 3.3.2 The Foundation Phase curriculum

- 3.4 LEARNING IN AN ADDITIONAL LANGUAGE

- 3.5 MULTILINGUAL LEARNERS WITHIN THE PRESCHOOL CONTEXT

- 3.5.1 The needs of the multilingual preschooler

- 3.5.1.1 The need for social interaction

- 3.5.1.2 The need for cultural recognition to develop self-esteem

- 3.5.1.3 The need to develop language

- 3.5.2 The role of parents or primary caregivers

- 3.5.2.1 Provide social context

- 3.5.2.2 Ensure L1 maintenance and cultural support

- 3.5.2.3 Provide continuity between school and home

- 3.5.3 The role of preschool teachers

- 3.5.3.1 Promote social interaction

- 3.5.3.2 Provide cultural support

- 3.5.3.3 Provide language stimulation

- 3.5.4 The role of speech-language therapists

- 3.6 CONCLUSION

- 3.7 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 4: COLLABORATIVE PARTNERSHIPS IN AN INCLUSIVE APPROACH TO THE ACQUISITION OF ENGLISH AS LANGUAGE OF LEARNING AND TEACHING

- 4.1 INTRODUCTION

- 4.2 AN ECO-SYSTEMIC MODEL

- 4.3 INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

- 4.4 COLLABORATIVE INTERVENTION

- 4.5 THE ROLE OF SPEECH-LANGUAGE THERAPISTS IN A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH TO INCLUSIVE EDUCATION

- 4.5.1 Assessing communication proficiency

- 4.5.2 Intervention planning

- 4.5.3 Facilitating language development

- 4.5.4 Role releasing

- 4.6 BARRIERS TO COLLABORATION FOR SPEECH-LANGUAGE THERAPISTS

- 4.7 CONCLUSION

- 4.8 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 5: METHODOLOGY

- 5.1 INTRODUCTION

- 5.2 CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK

- 5.3 MAIN AIM OF THE STUDY

- 5.3.1 First sub-aim

- 5.3.2 Second sub-aim

- 5.3.3 Third sub-aim

- 5.4 RESEARCH DESIGN AND METHOD

- 5.4.1 Research design

- 5.4.2 Research method

- 5.4.3 Data collection methods

- 5.5 ETHICAL ISSUES

- 5.5.1 Protection from harm

- 5.5.2 Informed consent

- 5.5.3 Right to privacy

- 5.5.4 Honesty with professional colleagues

- 5.6 RESEARCH PHASES

- 5.6.1 Phase One: Needs and strengths of preschool teachers and preschool learners

- 5.6.1.1 Research aim

- 5.6.1.2 Context

- 5.6.1.3 Teacher participants

- 5.6.1.4 Material and apparatus

- 5.6.1.5 Data collection

- 5.6.1.6 Response distribution

- 5.6.1.7 Data recording

- 5.6.1.8 Data analysis

- 5.6.2 Phase Two: Language and communication proficiency of multilingual preschool learners

- 5.6.2.1 Research aim

- 5.6.2.2 Context

- 5.6.2.3 Learner participants

- 5.6.2.4 Material and apparatus

- 5.6.2.5 Data collection

- 5.6.2.6 Data recording

- 5.6.2.7 Data analysis

- 5.6.3 Phase Three : The role of the speech-language therapist

- 5.6.3.1 Research aim

- 5.6.3.2 Data collection

- 5.6.3.3 Data analysis

- 5.7 VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY

- 5.7.1 Validity

- 5.7.2 Reliability

- 5.8 CONCLUSION

- 5.9 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 6: RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

- 6.1 INTRODUCTION

- 6.2 NEEDS AND STRENGTHS OF PRESCHOOL TEACHERS AND PRESCHOOL LEARNERS

- 6.2.1 Context-specific information

- 6.2.1.1 Description of participating preschools

- 6.2.1.2 Characteristics of teacher participants

- 6.2.1.3 Languages of preschool learners

- 6.2.2 The needs and strengths of preschool teachers in teaching multilingual preschool learners

- 6.2.2.1 Perception of problems

- 6.2.2.2 Perception of own competencies

- 6.2.2.3 Teacher participants’ training

- 6.2.2.4 Perception of support needs

- 6.2.2.5 Beliefs regarding L2 acquisition

- 6.2.2.6 Strategies to facilitate ELoLT comprehension

- 6.2.3 Summary of perceived needs and strengths of teacher participants

- 6.2.4 The needs and strengths of multilingual preschool learners

- 6.2.4.1 Multilingual preschool learners’ coping strategies to facilitate comprehension

- 6.2.4.2 Multilingual preschool learners’ socioemotional behaviours

- 6.2.4.3 Multilingual preschool learners’ receptive ELoLT skills

- 6.2.4.4 Multilingual preschool learners’ expressive ELoLT skills

- 6.2.4.5 Multilingual preschool learners’ pragmatic skills

- 6.2.5 Summary of the teacher participants’ perceptions of the needs and strengths of the multilingual preschool learners

- 6.3 LANGUAGE AND COMMUNICATION PROFICIENCY OF THE MULTILINGUAL PRESCHOOL LEARNERS

- 6.3.1 Learner participants’ language characteristics

- 6.3.1.1 Learner participants’ receptive ELoLT skills

- 6.3.1.2 Learner participants’ expressive ELoLT skills

- 6.3.1.3 Learner participants’ pragmatic skills

- 6.3.2 Summary of learner participants’ needs and strengths

- 6.3.3 Comparison of teacher participants’ perceptions with results of ELoLT proficiency assessment of learner participants

- 6.4 THE ROLE OF THE SPEECH-LANGUAGE THERAPIST IN THE ACQUISITION OF ELoLT BY MULTILINGUAL PRESCHOOL LEARNERS

- 6.5 CONCLUSION

- 6.6 SUMMARY

- CHAPTER 7: CONCLUSION

- 7.1 INTRODUCTION

- 7.2 CONCLUSIONS DRAWN FROM THE RESEARCH

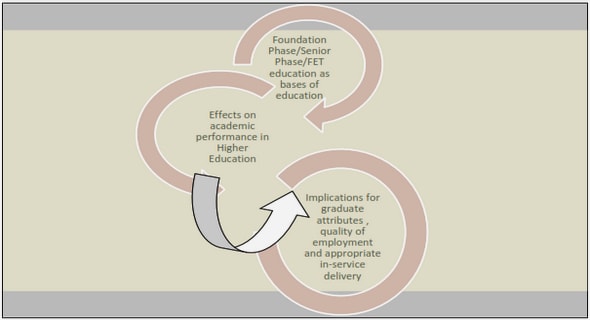

- 7.3 A SERVICE DELIVERY MODEL TO FACILITATE THE ACQUISITION OF ENGLISH AS LANGUAGE OF LEARNING AND TEACHING IN THE RESEARCH CONTEXT

- 7.4 CRITICAL EVALUATION OF THE STUDY

- 7.5 CLINICAL IMPLICATIONS OF THE RESEARCH

- 7.6 INTERVENTION GUIDELINES

- 7.7 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

- 7.8 FINAL COMMENTS

- REFERENCES

- APPENDICES

- APPENDIX A: QUESTIONNAIRE

- APPENDIX B: INITIAL LETTER TO TEACHERS

- APPENDIX C: FOLLOW-UP LETTER TO TEACHERS

- APPENDIX D: INFORMED CONSENT LETTER TO PARENTS

- APPENDIX E: ERROR ANALYSIS FORM

- APPENDIX F: TRANSCRIBED ELICITED LANGUAGE SAMPLE

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

MULTILINGUAL PRESCHOOL LEARNERS: A COLLABORATIVE APPROACH TO COMMUNICATION INTERVENTION