Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER3 RESEARCH APPROACH

Philosophy of Science and Methodology Seminar

It gradually became clear why the point of departure chosen for the ADP programme was each student’s unique professional problem. I began to see that the way practitioners define their research problems is subject to the unexpressed personal assumptions they hold and have to become aware of in their search for creative solutions. A positivist approach to research would thus not be useful for such a subjective self-research venture. The seminar on the Philosophy of Science and Methodology served to prepare us for a constructivist approach to research, which was what the ADP programme advocated. What follows is an account of the arguments in the philosophy of science that were dealt with during the course of the seminar. These discussions crystallized my awareness of how practitioners (or everyone, for that matter) actively construct their enquiries and interventions.

Our study of Chalmers23 brought it home that the notion of objectivity is essentially flawed. Hanson24, Kuhn25 and Popper6 , amongst others, have also seriously questioned the positivist belief that science is based on neutral observation. Observation statements are impregnated with assumptions which cannot be validated by empirical means. « Reality » exists only in the context of a mental construct for thinking about it. Thus scientific theory does not serve to map reality in any direct or decontextualized manner7 and these authors therefore deny the representational nature of knowledge.

These arguments support the notion of a constructivist28 epistemology. As Gergen29 comments, « the terms through which the world is understood are social artifacts – products of historically situated interchanges among people ». The degree to which a given form of understanding is sustained across time is not fundamentally dependent on rational proof. Descriptions and explanations are inherently part of various social patterns. They serve to sustain and support certain patterns to the exclusion ofothers. Thus, all theories are historically situated. There is also no neutral criterion by which the ultimate truth or falsity of different knowledge claims can be determined30 • Empirical evidence is « empirical » only in terms of the epistemological context in which it is generated, and not in any other, more enduring or universal, sense31 • In fact, there are many different ways in which reality can be constructed32 •

Clearly, the constructivist position has radical implications for research. If we are in fact constructing reality, research cannot be a matter of discovering it! Kell~3, who introduced personal construct theory to the fields of personality theory and mental health, insists that we should not confuse our inventions with discoveries. In describing the creation of his own theory, he explains that: « I must make this clear at the outset. I did not find this theory lurking among the data of an experiment, nor was it disclosed to me on a mountain top, nor in a laboratory. I have, in my own clumsy way, been making it up »34 • Watzlawick35 emphasizes a similar distinction when he suggests that objectivists are inventors who think they are discoverers. « Good » constructivists, by contrast, acknowledge the active role they play in creating a view of the world and interpreting their observations in terms ofie6• Because context and meaning are regarded as all-important, constructivists accept that all human pursuits are dialogues about the interlocking wants, desires, and expectations of all the participants. Thus, the goal of research becomes a pragmatic and political one, a search not for truth but for any usefulness that the researcher’s understanding of a phenomenon might have in bringing about change for those who need it37 • The constructivist therefore takes a practical approach to research and asks: Is the theory useful in my work? He or she also regards hypotheses that persist as, at best, part of a temporarily acceptable working framework38 As Rademeye~9 says:

Assuming that (a) each of us creates his/her particular reality, and (b) research is a matter of problem solving, it follows that each individual (practitioner) can (and should) take the role of researcher. By sharing individual experiences through collaborative action research, general guidelines for resolving certain types of problems are bound to develop. These, however do not hold the status of theories (as in the case of the « received view » of science) but are regarded as working hypotheses. Given the traditional connotation of the term « hypothesis », it might be useful to use the word « diathesis » instead. « Diathesis » signifies a disposition, a way of managing things.

The constructivist perspective ipso facto applies to us all; it is no esoteric idea. Kelly40 believed that each of us has the ability to notice the kinds of « templates » that we create and typically use to make sense of the world. He found it useful to characterize his role in therapy as that of « research consultant ». Instead of fixing problems, he wanted to co-investigate testable hypotheses about productive ways of living. He saw symptomatic behaviours as human questions that had lost their connective threads, which might have led the person to either a satisfactory answer or a better question. He wanted to help his clients to reformulate their questions, so that their enquiry could move forward again41 • No human being can step outside ofher or his humanity and view the world from no position at all, which is what the idea of objectivity suggests, and this is as true of scientists as it is of anyone else. It therefore becomes necessary for researchers to acknowledge, and even to work with, their own intrinsic involvement in the research process and the part this plays in the results that are produced42 •

Argyris and his co-workers43 raised the point that professional practitioners often display a tension between their « espoused theories » and their « theories-in-use ». Espoused theories are those that we use to explain or justify our behaviour – the theories that we claim to follow. Theories-in-use are those that can be inferred from our spontaneous action – the theories that we use and hold. The latter are usually tacit cognitive maps by which we design our action. This is aptly illustrated by the therapist’s tendency to perceive and to act in predictable ways under certain circumstances! Family therapists Kantor and Andreossi44 refer to the therapist’s « boundary profile », which is the somewhat discrete set of tendencies that govern his or her relationships. A specific set of internalizations derived from past experiences inculcate as well as account for such tendencies. These tendencies inevitably lead to the evolution of (often unarticulated) personal explanatory systems and constructions ofreality. Because these structures actively mediate between the therapist and his or her therapy techniques, they often have more bearing on therapeutic outcome than do the therapist’s more readily observable formal interventions that are derived from the therapist’s theoretical perspective.

Thus the practitioner’s unofficial theory is a determining factor in her work with clients. This theory is, naturally, tacit because it is characteristic of spontaneous action that most of the knowledge informing it remains tacit (or implicit). Polanyi45 , the first to use the phrase « tacit knowing », illustrated this by referring to our ability to recognize one face among thousands despite the fact that we cannot tell how we recognize the face we know. Schon46 speaks of the tacit knowledge embedded in recognitions, judgements and skilful actions as « knowing-in-action », and argues that it is the characteristic mode of ordinary practical knowledge. But he also notes that people sometimes reflect on what they are doing when they are puzzled or don’t get the results they expect. This « reflecting-in-action » is a way of making explicit some of the tacit knowledge embedded in action so as to figure out what to do differently. Hence the need to educate « reflective practitioners »47 • Schon48 argues for a new epistemology of practice that takes as its point of departure the competence already embedded in skilful practice -especially, the reflection-in-action that practitioners bring to situations of uncertainty, uniqueness, and conflict.

How is this to be achieved? Fortunately, educationists have shown the way in this regard. During the 1970s, teachers in England and Australia expressed their dissatisfaction with the prescriptive way in which educational theory was then being applied. They argued that established educational practice often failed them when they were confronted with unique, problematic classroom situations, and they expressed a need for theory to move closer to practice. They maintained, too, that their professional development needed to be approached from the « bottom They rediscovered the « Action Research » of Lewin50, whose ideas on the relationship between science and social change showed them a way of achieving their objective. Lewin argued that drastic changes were necessary in dealing with the social crises caused by World War He was keen to study social issues himself and to provide people with a way of engaging in their own enquiries into their relationships. This, he proposed, could be carried out according to a spiral of steps of planning, acting, observing and reflecting51 • Lewin’s description of action research allowed educationists to effect significant school reforms by applying action research in a naturalistic way. At the same time, they reaped major benefits such as personal and professional growth, a sense of empowerment and a release of creativity52 •

Stenhouse53 challenged armchair critics by inviting them to ascertain what changes to make in the schools by personally participating in and changing the practical situation54 • His central message for teachers was that, as the best judges of their own practice, they should become the researchers, and the natural consequence would be an improvement in education55• The teacher participates in his or her own enquiry, and collaborates with others as part of a shared enquiry, instead of trying to apply the results of research done by academics56 • In fact, it was recognized by Peters and Robinson57 that action research done in this way exemplifies a constructivist orientation. In their review of contemporary writers on action research, Peters and Robinson suggest that two versions of action research exist – a weak and a strong version. While most commentators see it as a research methodology or strategy (the weak version), others (more specifically, Kemmis, Elliot and Argyris) emphasize the emancipatory potential of social research and the central importance ofthe participants’ beliefs, values, and intentions (the strong version). The proponents of the strong version rejected the positivist notion of a neutral research endeavour. In the same vein, they changed the role of « research subject » to that of a « research collaborator ». They stress that « our understanding of the world is both social and constitutive, social actors who have created their own histories can also reflect upon themselves and their situation and transform or change their reality »58 •

Method

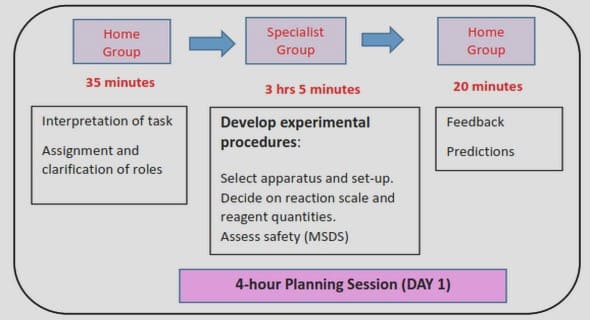

The second seminar gave us ample opportunity to start our self-research and to discuss our practices with fellow students and ADP staff members. The following steps describe the method that was assigned.

Problem description

As mentioned in chapter 2, we were asked to describe a « personal professional problem » which would serve as a reference point for our self-research. In order to identify such a problem, we were asked to write up case reports on several of our problematic cases and our attempts to solve them. We each analysed our case reports according to specific questions which Gert had devised.

Problem analysis

Following this fact-finding process, we were engaged in a rigorous analysis of the assumptions that we associated with our problematic situation – focusing particularly on the assumptions underlying our explanations of our problem situation and the values and inferences on which we based our problem-solving attempts. This was mostly facilitated through discussing with the group our personal history and how this linked with our personal service dilemma. This analysis aimed to make us aware of our « theory-in-use » and to put us in a position to make it explicit.

A somewhat similar approach to the supervision process with students working with some version of collaborative action research had been proposed by Marshall and Reason59 • Rather than providing « expert » advice on methodology, they concentrate on students’ personal processes as they engage with their research. In their view, good research is an expression of a need to learn and change, to shift some aspect of oneself. Such research cannot be done alone, as « we each need to be with others who can support and challenge our work, to be affirmed as enquiring persons and to know where we stand in relation to others »60 • The research supervision thus becomes part of the field of enquiry.