Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Food aid in Ethiopia

Ethiopia has been one of the world’s major recipients of international food aid for decades. As a result, over the last twenty years, food aid has amounted to one-tenth of domestic pro-duction in Ethiopia (Planel, 2005). For wheat, a major staple in the country, food aid has even reached 40 percent of domestic production.

Ethiopia has faced a major shift in food aid policy in the mid 2000s. Before that date, food aid was basically repeated emergency interventions. While those interventions were successful in terms of alleviating starvation, they did not prevent asset depletion and were not integrated in agricultural development activities (Berhane et al. , 2014).

Against this background, a number of policy changes have occurred. First allocation criteria of free food aid were reformed(DRMFSS, 1995, 2003). Before 2003 those who used to be eligible for free food delivery were the elderly, disabled persons, lactating or pregnant women, and hou-sehold members attending to young children. In 2003, the Disaster Risk Management and Food Security Sector revised the official guidelines and introduced the Household Economic Approach. This method is based on a survey that assesses hazard probability and coping strategies at the household level. For instance, it takes into account resources available to the household, such as assets (livestock) or relatives who could give transfers. While the Household Economic Approach is based on sound economic theory, it is hard to apply on the ground, partly because the ins-titutional channels through which aid is actually allocated have hardly changed (Shoham, 2005).

Secondly starting 2004-2005, Ethiopia, with the help of donors, implemented the Productive Safety Net Program (PSNP). This multi-year program seeks to prevent asset depletion at the household level and build assets at the community level ; it also ensures timely and predictable cash and/or food transfers to chronically food-insecure people. 4 The program covers now more than 50 percent of the communities (woredas) in the country. 5 The shift from “annual emergency aid » to an integrated safety net approach is likely to have influenced households’ marketing behavior and is worth studying over time.

Related studies on Ethiopia

As one of the countries most dependent on food aid, Ethiopia has been the focus of nume-rous studies.

A first stream of work focuses on targeting and dependency. Aid allocation in Ethiopia re-sults from a three-step process where the government decides the geographical allocation of aid at the regional level, regional leaders decide the allocation of aid by woreda, and local leaders at the Peasant Association (PA) level select households within each community. All steps are subject to inefficiency and potential political capture. According to Clay et al. (1999), Jayne et al. (2001) and Enten (2008), allocation at the woreda level results from negotiations between the government, the administrative staff and local communities and, as a result, is not (entirely) related to effective needs. These three papers, although written ten years apart, show that the Tigray region has been favored because of its close ties to the government. 6 At the local level, re-cipient households with political connections and involved in village organizations receive more food aid than recipient households without connections (Broussard et al. , 2014). The system perpetuates itself, as PA leaders who are elected are reportedly manipulating the election, by threatening voters that they will be excluded from federal support (Human Rights Watch, 2010).

Two consequences emerge from these papers on allocation process in Ethiopia. First, tar-geting is likely to be imperfect. Only 22 percent of food-insecure people received some aid ; this comes either because their district was not targeted or because their household was not selected (Planel, 2005). As allocation under the new Household Economic Approach relies less than before on easily households’ observable characteristics such as age and gender, it may be subject to political capture.

4. The first year of implementation of the PSNP has coincided with a large increase in both the number of households receiving food-for-work and those receiving free food transfers. The PNSP was to be complemented by improvements in access to credit and seeds that were included in the Other Food Security Programme (OFSP). The latter lacked sufficient agricultural extension agents and the coverage was limited. Hence, the OFSP was redesigned in 2009 and a new program was introduced, called the Household Asset Building Program (HABP).

5. A woreda is an administrative unit, defined below region and zone, and roughly equivalent to a district elsewhere. Woredas are composed by kebeles (group of villages) and peasant associations (PA). In order to obtain land, households have to register with the PA which keeps the list of recipient households. A peasant association can cover many villages. For instance, the Adele Keke PA consists of 28 villages.

6. Politically motivated aid allocation is of course not restricted to Ethiopia. For instance, in Madagascar, regions with close ties to the government receive more aid (Francken et al. , 2012) .

Second, because of political stability in Ethiopia, with a national coalition staying in power for many years, it is likely that the same politically-connected households have received aid over time. Hence, the part of the selection that is based on unobservable households characteristics such as political connections may be considered as time-invariant.

Political capture is not the only culprit of poor targeting. The fixed costs of setting operations and identifying needs also account for the inertia of food aid allocation. Jayne et al. (2002) show, based on a nationally representative rural dataset of 1996, that the spatial allocation of aid in 1996 is highly correlated with the spatial pattern of vulnerability in 1984 during the famine and is concentrated in areas that are not the poorest. The inertia is particularly prevalent for food-for-work, possibly because the latter is often a multi-year program.

Asfaw et al. (2011) investigate the determinants of participation in food aid programs and the impact of such programs on poverty reduction, based on the ERHS surveys from 1999 and 2004. They show that households’ size and asset endowments determine the extent of poverty alleviation and food aid dependency. Based on quantitative and qualitative data from 1999-2000 and 2002-2003, Little (2008) finds that food aid plays a significant role in households’ recovery strategies, without creating dependency. This is due to the fact that aid deliveries are poorly timed and come with uncertainty. Bevan & Pankhurst (2006) have conducted interviews in 20 villages, including the villages surveyed in the ERHS. Their study gives a sense of attitudes towards aid. Respondents mention that aid in the long-term can make « people lazy ». They also claim that food aid may come too late, is insufficient and distributed in centers that are too far away.

A second stream of literature investigates the impact of food aid on food prices and food production. Levinsohn & McMillan (2007) argue that the impact of aid on poverty depends on its effect on prices and on the household being a net seller or a net buyer. Based on two nationally representative household surveys in 1999-2000, they estimate the welfare impact of a change in prices and infer the impact of food aid on prices using a partial equilibrium model. They find that aid is alleviating poverty in the short term, as net buyers are more numerous than net sellers and poorer. Kirwan & McMillan (2007) extend the time span of the previous analysis to the period 1970-2003 and use indirect evidence based on aggregate data on production and prices. They find no correlation between food aid and producer prices, the latter declining stea-dily after 1984 while food aid, mostly driven by variations in the US price of wheat, has been volatile. As a consequence, food aid might have an impact on long-run production, not through prices but because of uncertainty about shipments that might have deterred investment in the wheat sector. Re-examining the relationship between aid and prices, Assefa Arega & Shively (2014), using monthly data over 2007-2010, do not find an impact of food aid on local producer prices of wheat, teff and maize in Ethiopia.

Using a computable general equilibrium model calibrated to Ethiopia in 2000, Gelan (2006) finds a disincentive impact of food aid on domestic food production. Removing food aid stimu-lates demand and generates an expansion of the food producing sector with a slight increase in producer prices. In general equilibrium, consumers would substitute between grains ; as house-holds receive wheat for free, they would shift away from maize or teff, hurting not only wheat growers but also the producers of other cereals.

Abdulai et al. (2005) re-examines the impact of aid on food production both at the micro level on Ethiopia and at the macro level with a VAR model estimated on 42 Sub-Saharan Afri-can countries. They do not find evidence of a disincentive impact with either method. If any, the macro analysis tends even to find a positive impact of food aid on production one or two years later. The micro analysis is based on two rounds of the ERHS in 1994 and one in 1995. They estimate the impact of receiving food aid on various outcomes: labor supply (of various sorts: on-and off-farm, wage work and own business, male and female), agricultural investment and use of inputs, and informal labor sharing. Some of these outcomes are of a 0/1 type. Others are conti-nuous with zero values, and are estimated with a tobit. A naive estimation finds that aid has a strong disincentive impact. However, once controlled for household characteristics that might explain aid allocation (location, age, gender and education of household head, household size and holdings of land and oxen), only one impact remain significant (and positive), on off-farm female wage work. Then they estimate a model where aid is endogenous and is instrumented by past aid, reflecting an inertia effect as in Jayne et al. (2002). Aid received one year before, in early 1994, has a small disincentive effect on family labor supply for permanent and semi-permanent crops. On the contrary, contemporaneous aid (that received in 1995) has a positive impact on the same type of labor supply. Both past and current aid increase male labor supply of off-farm work. Overall, these findings make a very convincing case on the convergence of macro and micro analysis and the non existence of disincentive effects of aid in Ethiopia, at least in the short run.

Recent papers focus on the PNSP (Gilligan et al. , 2009; Hoddinott et al. , 2012; Berhane et al. , 2014) using propensity score matching and difference-in-difference estimations. The propensity score matching is based on observable households’ characteristics. It also accounts for unobservable characteristics at the village level, as it compares treated and control hou-seholds from the same woreda. The first paper finds a weak impact of PNSP in its first year of implementation in 2006 because of delays and under-payment of transfers. Aid recipients tend to increase their livestock suggesting a positive impact of aid on production. The second paper finds a positive impact of the PSNP on agricultural inputs use, especially when it is coupled with the OFSP extension program. The third paper considers treatment as continuous: it is the number of years of PNSP transfers. The paper compares the outcome between one and five years of PNSP. The propensity score is based on the demographic characteristics of the households before the program. Aid has a positive effect on food security and livestock holdings.

A third direction in the literature compares the different types of aid (Yamano et al. , 2000; Gilligan & Hoddinott, 2007; Bezu & Holden, 2008). For instance, food-for-work (FFW) target household members that are able to work and provide them a job with payments usually in-kind. If work requirements are harsh, not all eligible households enroll in the program, thus, there is self-selection on top of eligibility criteria. By contrast, free distribution is aiming at those that cannot work, children or elderly people. Bezu & Holden (2008) finds that food-for-work has encouraged the adoption of fertilizer in Tigray in 2001. They estimate a Heckman two-step model where first the household decides whether to adopt fertilizers, before deciding the actual quantity, conditional on selection. Gilligan & Hoddinott (2007) compares two programs that were expanded after the 2002 drought, free food distribution (FFD) of the « Gratuitous Relief », and food-for-work (the « Employment Generation Scheme » or EGS). They use the 1999 and 2004 waves of the ERHS and estimate a propensity score. They find that EGS participants had significantly lower growth of livestock holdings ; the effect is partly driven by outliers (some hou-seholds with large livestock in the control group). Households could also have decreased their precautionary saving as they felt protected and insured by aid. On the other hand, free food distribution was better targeted and smaller in size and had no significant impact on livestock.

Yamano et al. (2000) also distinguish between FFW and free distribution and examine their impact on purchases and sales separately. They argue that looking at net sales is not sufficient in order to assess the impact on local markets. They find that FFW decreases the purchase of wheat, while free distribution decreases the level of sales albeit the effect is small and not statistically significant.

To push their argument one step further, one would like to examine other types of market participation, such as households that grow wheat for their own consumption. Moreover, aid might not only influence the quantities sold or bought, but also the 0/1 decision of the type of market participation, for instance, determining producers who were growing wheat for their own consumption, to sell on the local market. Moreover, Yamano et al. (2000) were not controlling for the endogeneity of aid allocation. Last, we would like to take advantage of a panel stretching over 1994 and 2009 and contrast the short-run and the long-run impact of aid as well as look for any change in households’ behavior following the reform of aid policy in Ethiopia in the mid 2000s.

7. Another differentiating characteristic of food aid is whether it is sourced from local or regional procurement (LRP) or shipped from overseas. Lentz et al. (2013) show that LRP aid reduces delay and improves the adequacy between needs and shipments ; thus, it should reduce the risk of disincentive effect. Violette et al. (2013) show that LRP is more culturally accepted. This may reduce the negative impact on markets, as households are more likely to consume LRP aid instead of selling it, a consequence that is not investigated in their paper. Garg et al. (2013) examines the potential price effect of LRP aid and do not find any statistically significant impact. Unfortunately the EHRS does not provide information on the type of procurement. At the country level, one quarter of aid in wheat comes from local purchases (INTERFAIS-WFP).

Data and descriptive statistics

Our data comes from the Ethiopian Rural Household Survey Dataset (EHRS), a longitudi-nal survey which covers some villages between 1989 and 2009. The survey results from a joint project between Addis Ababa University, the CSAE at the University of Oxford and IFPRI. The data are not nationally representative but account for the diversity of non-pastoral farming systems in the country (see Dercon & Hoddinott (2009) for more details). The survey gives information on household characteristics, agriculture and livestock, food consumption, transfers and remittances, health, women’s activities, and information at the village level on electricity and water, health services and education, wages, production and marketing.

Most of the results of this paper are based on a balanced panel of 1215 households in 15 villages, followed over 5 rounds (in 1994, 1995, 1999, 2004 and 2009). 8 In the robustness checks, we also run the estimations on the whole (unbalanced) sample.

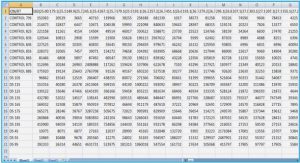

Table 1.1 provides descriptive statistics of the sample. The poverty rate was 48.2 percent in 1994, decreased in the late 1990s and early 2000s, but has returned to its previous level in 2009. Households are cultivating 1.5 hectares on average. The worst harvest took place in 1995 with only 533 kgs of wheat produced by the average household, and the best in 2009 with a production three times higher. The size of livestock holdings has increased continually since 1994 and reaches an average of 5 tropical livestock units in 2009 (one tropical livestock unit – TLU – equals 1 cow or 10 goats or 11 sheep or 100 chickens).

The variables of interest are whether a household has received free food aid or food-for-work, and the quantities received. We focus on one crop, wheat, which is one of the major cereals in Ethiopia. From the mid-1990s, wheat consumption has increased steadily in both urban and rural areas and wheat has become one of the top priority crops deemed to solve food security challenges in the country (Tefera, 2012). Thus, a large share of food aid is provided in wheat (74 percent in our sample).

The share of recipients is highly variable: only seven percent of households received free food aid in 1995 whereas almost 30 percent did so in 2009. 10 Hence, on average, only one third of

8. We drop the second round of EHRS (December 1994-January 1995), as its reference period was six months instead of one year, and the fourth round (1997), which surveyed additional villages. However we include pro-duction, sales and food aid of the second round in order to compute the annual quantities in 1995.

9. At the national level, aid in wheat represents about 72 percent of total food aid from 1988 to 2011 (INTERFAIS-WFP).

10. In 1995, total food aid distributed across the world dropped as the US reduced its shipments because of a spike in food prices.

Data and descriptive statistics

The share varies between villages as well, from zero to almost 80 percent. Quantities of wheat received per household vary from 30 kilograms in 1995 to 100 kilograms in 1999. The share of household benefiting from food-for-work programs was stable during the 1990s at around 10–11 percent. It has doubled after 2004.

Looking at targeting criteria (Table 1.3), recipient households have fewer and older members. They have fewer children on average, though we would have expected the opposite, given the official allocation guidelines before 2004. Food-for-work and free food aid recipients seem to differ in terms of agricultural assets and household composition. Households receiving free food are smaller than those receiving food-for-work but have more old-age members. Food-for-work households, as expected, cultivate less land than other households and have less livestock.

Regarding households market participation, we define four groups. First, households can be wheat buyers or sellers (these categories are defined in gross terms). They can grow wheat for their own consumption, without selling or buying it: these households are called « autarkic ». Finally, they can be « non-involved » (in any wheat-related activity), meaning that they neither produce nor buy wheat. Household are considered as producers if they sow wheat, even if they get no harvest.

All four types of market participation are present in Ethiopia. 12 The share of households cultivating wheat (for their own use or to sell) increases over time, going from 24 percent in 1994 to 32 percent in 2009. 11 percent of households were sellers and 18 percent buyers in 2009 ; 20 percent were in autarky and 55 percent were « non-involved ». As buyers and sellers are defined in gross terms, they might overlap (as some households are doing both) but these are in very small number, making up less than four percent of the sample.

Households’ market participation status is not stable across rounds (Table 1.4). Transition happens mostly between buyers and non-involved households, and to a lesser extent between sellers and autarkic households. In addition, only three-quarter of households that have grown wheat at time t cultivate it again at time t + 1 (not reported in the Table).

11. 2004-2005 marks the end of a long drought and the first implementation year of the PSNP.

12. The exception is 1995, when the data shows no autarkic households and a large increase of the number of sellers. One reason might be a policy shift that has enhanced incentives to sell: « In the 1995/96 season, the Ethiopian Grain Trading Enterprise was explicitly mandated to support producers’ maize and wheat prices at the stated support price » (Negassa & Jayne, 1997). In the robustness check, we present the estimations without 1995.

In the descriptive statistics, food aid recipients differ from other households in terms of their market participation status. Beneficiaries are more likely to be non-involved in wheat-related activity and less likely to be autarkic households or sellers (Table 1.5). They are as likely to buy wheat. Regarding quantities, aid recipients produce less (the difference being significant at 1 percent level of confidence for autarkic households) ; they also buy more wheat. However, they sell as much as non-recipient households. How much of these differences come from selection and endogenous aid allocation and how much could be triggered by aid itself?

Table of contents :

General Introduction

1 Does Food Aid Disrupt Local Food Market? Evidence from Rural Ethiopia

1.1 Introduction

1.2 Context

1.2.1 Food aid in Ethiopia

1.2.2 Related studies on Ethiopia

1.3 Data and descriptive statistics

1.4 Empirical specification

1.4.1 On production

1.4.2 On sales and purchases

1.5 Results and analysis

1.5.1 On production

1.5.2 On sales and purchases

1.5.3 Robustness checks

1.6 Conclusion

1.7 Figures and tables

1.8 Appendix

2 Donors Versus Implementing Agencies: Who Fragments Humanitarian Aid?

2.1 Introduction

2.2 Humanitarian aid: data and descriptive statistics

2.2.1 Data

2.2.2 Descriptive statistics

2.3 Fragmentation of humanitarian aid

2.3.1 Indicators of aid fragmentation

2.3.2 Donor and implementing agency fragmentation

2.4 Delegating aid and its fragmentation: potential consequences

2.4.1 Positive impacts of delegation and fragmentation on aid efficiency

2.4.2 Negative impacts of delegation and fragmentation on aid efficiency

2.5 Three case studies of implementing agency fragmentation

2.5.1 Haiti 2010: the burden of fragmentation

2.5.2 Pakistan 2010: a useful fragmentation

2.5.3 Sudan 2010: the leading role of the UN

2.6 Conclusion

2.7 Figures and tables

3 To Give or Not to Give? How Do Donors React to European Food Aid Allocation?

3.1 Introduction

3.2 Empirical strategy

3.2.1 Specification

3.2.2 Instrumental strategy

3.2.3 Potential concerns

3.3 Data and descriptive statistics

3.3.1 Food aid statistics

3.3.2 Controls

3.4 Empirical results

3.4.1 Baseline results

3.4.2 Bilateral reactions

3.4.3 Placebo tests and robustness checks

3.5 A donor typology

3.5.1 Setting

3.5.2 Reaction function

3.5.3 Typology

3.6 Conclusion

3.7 Figures and tables

3.8 Appendix

General Conclusion