Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Chapter 2 Justification of the Study

The results of a study that addressed landowner awareness of federal tax law concerning forestry operations in South Carolina were recently published (Greene et al. 2002). In the study the awareness and use of seven federal income tax provisions among South Carolina nonindustrial private forest landowners were estimated. The data collected for the survey were gathered by mail surveys using the Dillman (1978) mail survey method. The study was implemented due to concern that many landowners actually knew little about or used the provisions available to them for the purposes of reducing the cost of forest management.

The seven tax provisions that landowners were asked about are as follows:

- Treatment of qualifying income as a long-term capital gain

- Annual deduction of management expenses

- Depreciation and Section 179 deduction for income-producing property

- Deductions for casualty losses or other involuntary conversions

- The reforestation tax credit

- Amortization of reforestation expenses

- The ability to exclude qualifying reforestation cost-share payments from gross

In addition, demographic data were gathered about the number of acres owned by each landowner, the primary reason for owning the land, whether the landowners were members of a forest owner organization, whether the landowners had written management plans, landowner occupation, age and total household income.

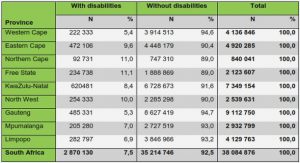

Results of the study indicate that landowners surveyed were more financially motivated and more active in management than the average landowner in the United States when compared to Birch’s (1996) demographic work concerning forest landowners in the United States. As a result, Greene et al. (2001) estimated that levels of awareness and use of the tax provisions, though low, were probably overly optimistic (Table 2-1).

A large percentage of landowners were not aware of several of the provisions available to them (Table 2-1). Of particular concern was a lack of awareness about depreciation and the section 179 deduction, the reforestation tax credit, reforestation amortization provision and exclusion of cost-share payments from gross income (Table 2-1).

Even though overall awareness of some of the provisions was low, results of the study show that large percentages of landowners that were aware of certain provisions tended to use them. Therefore, the authors concluded that if their results were representative, they were a call to forestry professionals to increase efforts to inform landowners of their tax options for reducing the cost of forest management.

Importance of Understanding the Impact of Taxes on Forest Landowners

Two major determinants of future U.S. timber production and non-timber forest outputs are 1) the proportion of land that remains covered in forests, and 2) the level of management and care given to those forests (Alig and Wear 1992). Forestlands in the United States are divided between public lands, industrial lands and non-industrial lands. The amount of timber produced by America’s forests depends significantly on the quality of management given to NIPF lands. A gap has existed in the past between the investment potential and the level of management on these private lands. Alig and Wear noted that the gap has been explained by: “1) lack of available investment capital, perception of forestry as a relatively risky enterprise, 3) relative lack of liquidity of the assets in young forests, 4) uncertainty about future prices of forest products and 5) important returns to forest ownerships that are not captured in a financial analysis of timber investments.” They noted that these issues would have to be addressed by forest policy in order to increase timber production.

Effects of Taxes on Markets and Individual Firms

At the market level, basic economic theory shows that taxes on producers usually shifts the supply curve to the left (Figure 2-1). When the shift occurs, the market equilibrium point shifts to the left as well, and the price of the product increases. The result is higher prices and lower production (Figure 2-1).

Under economic theory, firms are price takers when 1) firms in a specific market sector are producing identical products, 2) many firms exist in that market sector, 3) each 8 firm produces a small amount of the total supply and 4) no barriers of entry exist (Gwartney et al. 2000). When a firm is a price taker, it will expand output in the short run until its marginal revenue is equal to its marginal cost (Figure 2-2) in order to maximize profit (Taylor 2002). Income taxes serve to reduce marginal revenue or price (Gregory 1987). Therefore, the imposition of an income tax causes the price the firm receives to decrease. This is seen in the price change in Figure 2-2. As a result, optimum production in terms of profit decreases.

Private Landowners

Under the above definition, forest landowners are price takers when they sell timber. For example, a forest landowner growing and managing pine will grow a product similar to other landowners growing and managing pine. His timber output will supply only a small portion of the total timber production. Thousands of landowners exist who grow and manage pine, and individuals are free to sell and purchase forest property. If landowners behave as a firm, the effects of tax would be similar to those described for firms above.

Most landowners who produce timber, however, do not produce as a business or a firm. Landowners are a very diverse group of people who hold timberland for a variety of reasons, but a large portion of landowners have sold timber in the past (Birch 1996). Newman and Wear (1993) found that “NIPF behavior is consistent with profit maximization” when comparing NIPF behavior to the behavior of industrial landowners. However, they also found the production function of NIPF’s to be different than that of industrial landowners and suggested that the difference was due to “significant nonmarket benefits” received by NIPF landowners from their forests.

Birch (1996) found that 34 percent of U.S. private forest landowners said they never intended to harvest. However, this proportion of landowners only controlled 23 percent of the private forestland. Interestingly, Birch also reported that 46 percent of private landowners had harvested timber on their lands, and that this 46 percent controlled 78 percent of the private forest land in the U.S. Because landowners are profit motivated to some degree, the assumption is made that taxes serve as impediments to managing their forests. Thus, taxation significantly influences forest management practices, and landowners view taxation as an obstacle to meeting management goals.

Taxation

Forest landowners must deal with several kinds of taxes: income tax, property tax, transfer taxes and, in some cases, sales and use taxes. Taxation serves as an impediment to forest management in several ways. First, any tax paid on stumpage reduces the landowner’s revenue and has the tendency to reduce the owner’s interest in investing in timber production (Gregory 1987). Hibbard and others (2003) noted that the ability of the U.S. private forest to continually produce “economic and ecological outputs and services” was a function of the amount of investment made in terms of protection, use and management. A substantial proportion of income earned by firms and households is never available for consumption or investment. Instead, it is distributed to governmental units as tax revenue (Clutter et al. 1983). Second, tax law is complex, and professional help is often required in order to comply with the law. Most individuals who manage substantial forest land find assistance from professional tax specialists essential when doing their tax planning and return preparation (Clutter et al. 1983). Learning the relevant tax implications on management decisions and becoming familiar with incentives and how to use them is time consuming and costly (Bailey 1999). He noted the consequences of not taking advantage of existing incentives and policy can be even more expensive. Bailey (1999) found that taking advantages of tax incentives significantly increases the land expectation value of forestland. Third, focus on tax avoidance sometimes influences forest landowners to place the family forest in a legal or business structure that is less than optimal in terms of efficient management. However, although taxes do tend to serve as impediments to forest management, the nine federal income tax provisions addressed in this study offer several advantages and benefits to forest landowners that many taxpayers do not have. The purpose of the discussion involving taxes above is not to say that taxes are bad or that the tax burden on forest landowners should be further reduced. Rather the purpose is to demonstrate how federal taxation can affect forest management. Because the nine provisions do significantly reduce the forestlandowner’s tax burden, knowledge about the provisions is critical.

Income Taxes

Income taxes are a tax on earnings (productivity). Fortunately, profit from timber management can be treated as capital gain (if held for longer than one year and disposed of correctly). Profit from hunting fees and recreation is taxed as ordinary income. Tax policy concerning timber may favor timber management as an investment compared to other alternatives, which produce ordinary income. Capital gains rates are currently 15 percent. Bailey (1999) found ensuring capital gains treatment of timber sales to be crucial in obtaining the highest return on timber management investments. Bailey used discounted cash flow methodology as the decision criterion to examine the effects of income taxes on forest management profitability of various scenarios. He created a hypothetical scenario in which a landowner in the western U.S. who made $70,000 per year at his job and had an 11 percent discount rate engaged in an even-age forest management regime on his property. Bailey found that a landowner that failed to treat timber as a capital gain reduced LEV by 30 percent.

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION.

OBJECTIVES

PART I. INTRODUCTION TO TAX

CHAPTER 2 JUSTIFICATION OF THE STUDY.

IMPORTANCE OF UNDERSTANDING THE IMPACT OF TAXES ON FOREST LANDOWNERS

EFFECTS OF TAXES ON MARKETS AND INDIVIDUAL FIRMS

PRIVATE LANDOWNERS

TAXATION

INCOME TAXES

AWARENESS OF PROVISIONS ALLOWS FOREST LANDOWNERS TO MORE ACCURATELY ASSESS THE COSTS AND BENEFITS OF FOREST MANAGEMENT

CHAPTER 3 LITERATURE REVIEW

TIMBER TAX PROVISIONS

Capital Gains

Depletion

Deduction of Annual Forest Management Expenses

PASSIVE ACTIVITY LOSS RULES (PALS)

PAST TIMBER TAX RESEARCH

CHAPTER 4 CURRENT TAX LAWS.

IMPORTANCE OF UNDERSTANDING YEAR-TO-YEAR CHANGES IN TAX LAW

THE JOB AND GROWTH TAX RELIEF RECONCILIATION ACT OF 2003

FEDERAL INCOME TAX RATES FOR 2003 AND 2004

PART II. TAX CALCULATIONS AND LEV ANALYSIS

CHAPTER 5. EXAMPLES OF TIMBER SALE COSTS INCLUDING THE ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX

A TYPICAL SOUTHERN TRACT

ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX.

CHAPTER 6 EFFECT OF FEDERAL INCOME TAXES

– LEV ANALYSIS OF CASE STUDIES

ALLOCATION OF COSTS IN THE LEV ANALYSIS

AFTER-TAX DISCOUNTED CASH FLOW MODEL

INTENSIVE FOREST MANAGEMENT REGIME – SCENARIO ONE

LESS INTENSIVE FOREST MANAGEMENT REGIME – SCENARIO 2.

OTHER FOREST ACTIVITIES.

LANDOWNER SCENARIOS

INFLATION

ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX.

FINANCIAL ANALYSIS

RESULTS OF LEV ANALYSES ON INTENSIVE CASES

RESULTS OF LEV ANALYSES ON NON-INTENSIVE CASES

SUMMARY OF THE FOUR CASES.

CHAPTER 7 COMPLEXITY OF TAX LAW COMPLIANCE

WAGES SALARIES AND TIPS – W-2

BUSINESS INCOME OR LOSS – SCHEDULE C

CAPITAL GAIN OR LOSS – SCHEDULE D

ALTERNATIVE MINIMUM TAX – FORM 6251

CONCLUSION

PART III. LANDOWNER SURVEY METHODS AND RESULTS

CHAPTER 8. MATERIALS AND METHODS.

AMERICAN TREE FARM SYSTEM.

DILLMAN METHOD.

STATISTICAL ANALYSIS..

SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION

CHAPTER 9. NATIONWIDE RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN TREE FARM SYSTEM MAIL SURVEY

NATIONWIDE RESULTS.

USE OF A TAX PREPARER

DEMOGRAPHICS

CHAPTER 10 RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN TREE FARM SYSTEM MAIL SURVEY – SOUTHERN REGION

SOUTHERN REGION RESULTS.

USE OF A TAX PREPARER

DEMOGRAPHICS.

CHAPTER 11 RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN TREE FARM SYSTEM MAIL SURVEY – NORTHERN REGION

NORTHERN REGION RESULTS

USE OF A TAX PREPARER

DEMOGRAPHICS

EDUCATION

CHAPTER 12 RESULTS OF THE AMERICAN TREE FARM SYSTEM MAIL SURVEY – WESTERN REGION.

WESTERN REGION RESULTS

USE OF A TAX PREPARER.

DEMOGRAPHICS

CHAPTER 13 A COMPARISON OF ATFS AND FOREST LANDOWNER DEMOGRAPHICS AS DESCRIBED BY BIRCH.

PRIVATE FOREST-LAND OWNERS OF THE UNITED STATES (BIRCH 1996).

ATFS MEMBERS COMPARED TO TYPICAL U.S. LANDOWNERS.

ATFS DEMOGRAPHIC CHARACTERISTICS

HYPOTHESIS TESTS.

CHAPTER 14 CONCLUSION

REFERENCES.

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

FEDERAL TIMBER INCOME TAXES AND PRIVATE FOREST LANDOWNERS IN THE U.S.