Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 3 THE LEGISLATIVE AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA

INTRODUCTION

The discussion below gives a broad overview of land reform issues in the Third World, with a focus on Africa. The discussion then narrows to South Africa where the focus is specifically on a number of legislative and policy frameworks that impact both directly and indirectly on land reform delivery and the gendered aspects thereof. Firstly, it will review legal mechanisms for land reform and more specifically those dealing with land redistribution. Of major importance here is the White Paper on Land Reform Policy of 1997 (South Africa 1997a). Secondly, it will look at the role of the World Bank in shaping land reform policy in South Africa. Thirdly, it will look at the role of Government’s Growth and Employment Strategy (GEAR) in facilitating or hampering land reform delivery.

THE LAND QUESTION IN THE THIRD WORLD

Land reform has taken various forms in different countries. Prior to the 1990s, land reform in some countries was not a significant programme but in the 1990s it emerged as an important component of national development policy (Borras 2005; Borras et al 2007). For example, in Brazil and the Philippines, there have been state-driven attempts at land redistribution (Borras 2005).

Both countries have also witnessed strong military dictatorships, peasant movements and the rise of rural social movements agitating for reform in the land sector (Borras 2005). Market-led agrarian reforms have been implemented side by side with the state-driven land reform programmes. Some countries have experimented with land reform in the past, within a broad capitalistic framework (Bush 2002). Examples are Bolivia and Egypt, where land reform did not result in significant impact on poverty reduction and it is for this reason that they are confronted by important changes in land policy regimes (Borras 2005; Borras et al 2007; Jacobs 2010).

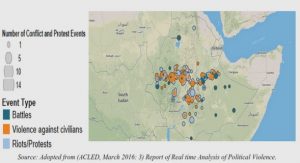

Other countries, such as Ethiopia, implemented land reforms with socialist inclinations but are now promoting varying degrees of market-oriented land policies. In some countries with a long history of colonisation, new land policies have had to be developed when the new post-colonial state came into being. Examples here are Namibia, Zimbabwe and South Africa (Moyo & Yeros 2005). In these countries land reform has been shaped by the way colonialism ended, as well as by the character of the nationalist government that came into power (Moyo & Yeros 2005; Lahiff 2007). All these countries were, in the early stages, forced to adopt the market-oriented land policies. The policies have been replaced by more radical land policies in Zimbabwe, for example, where large amounts of land were expropriated through the “fast track land reform programme” (Moyo & Yeros 2005; Worby 2001).

It has been demonstrated in Chapter One that governments in Africa experimented with land reform without success (Lund et al 1996) and that this was replaced by the market-led approach advocated by the World Bank which have not yielded successes either (Fortin 2005; Lund et al 1996; Shipton 1988).

BACKGROUND TO LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA

Prior to 1994 there were various debates on the land question in preparation for a democratic post-apartheid state (Cliffe 1992; Cooper 1992). Why was land reform important for South Africa? The answer lies in the history of colonisation when in the late 1880s and early 1900s mechanisms were instituted by the various colonial governments to systematically dispossess Africans of their land (Legassick 1976; Bundy 1979). Bundy, in his 1979 celebrated work The Rise and Fall of the African Peasantry, and Mbeki (1984), argue that Africans were successful farmers who had ventured into sharecropping schemes with white South Africans and it was this very success that led to their downfall. Sharecropping was a system of agriculture where land owners allowed their African tenants to use their land in return for a share of the crops. The political and economic pressures for land reform grew out of this history of colonial dispossession in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries and the racial pattern of land ownership that successive white minority governments enforced after 1910 (Walker 2003; Ntsebeza 2007; Wolpe 1972).

With the discovery of minerals, especially gold in the 1880s, systematic attempts were made to compel Africans to become wage labourers in the growing gold mines and capitalist economy (Ntsebeza 2007). Of major significance here was the Native Land Act of 1913 which sought to reduce competition from the black peasant producers by dispossessing them of their lands (Bundy 1979). The Act set aside scheduled or segregated areas for African occupation. These were first referred to as the Reserves and later as Bantustans in the latter part of the twentieth century. Africans were forbidden from buying or owning land on these reserves and were placed under the control of chiefs who imposed on them by the government of the day (Ntsebeza 2007).

According to Bundy (1979:46; Ntsebeza 2007), the abolition of sharecropping, which had worked well prior to the Land Act of 1913, as well as Africans’ inability to access land outside the reserves, all led to the fall of the peasantry in South Africa. Ultimately, Africans provided cheap labour power to the growing white-owned commercial farming sector and to the growing capitalist economy, while maintaining strong links to the countryside (Legassick 1976; Bundy 1979). The legislation enacted by the apartheid state perpetuated and gave rise to overcrowding, landlessness and mass poverty in the reserves which became the home for victims of forced removals of “black spots” from “white territory” (Legassick 1976).

It was, therefore, not surprising that immediately after the first democratic election in 1994 in South Africa, the new ANC-led government would embark on a wide-ranging and ambitious programme of transformation of the countryside through the Reconstruction Development Programme (ANC 1994; Aliber 2003:471). A major tenet of the Reconstruction and Development Programme (RDP) policy framework was the need to reduce the poverty affecting millions of South Africans, thereby redressing inequalities and injustices of the past (Aliber 2003:472; May 2000; Turner & Ibsen 2000). One damaging legacy of past discriminatory apartheid policies is the inequitable distribution of productive assets, including land, between race groups which meant that land had become a source of social tension (Aliber 2003; Ntsebeza 2007). Many rural people are landless, and even those with small pieces of land are unable to produce for both subsistence and commercial purposes. It was only logical that access to land, through land redistribution, tenure reform and land restitution, was one of the main priorities highlighted in the RDP document. Land redistribution, more than the other two approaches to land reform, became the central and driving force envisaged in the RDP document (May 2000).

The RDP’s main aim was to involve all people in a process of empowerment that led to equality in gaining access to resources (Rangan & Gilmartin 2002). It identified land and agrarian reform as the most important issue facing the new government (Hargreaves & Meer 2000; Rangan & Gilmartin 2002; Walker 2003). The RDP was, however, replaced by a growth, employment and redistribution strategy (GEAR) (Bond 2000). This strategy placed greater emphasis on using market mechanisms to create employment opportunities, redistribute assets, reform state institutions and reduce poverty in the rural and urban areas (May 2000:21). It also reiterated a commitment to gender equity in land reform by supporting women to undertake market-oriented farming, training and capacity-building on land-related matters (Turner & Ibsen 2000).

Even though issues of land were a major topic in scholarly articles, prior to 1994, the ANC did not produce any substantial land and agrarian policies in anticipation of a post-apartheid South Africa and land reform did not feature prominantly on the ANC agenda (Bond 2000; Weideman 2004:5). Bond (2000) argues that it is for this reason that it was easy for the ANC to replace RDP by GEAR. Although RDP offices were set up in the President’s office, charged with the responsibility of coordinating RDP activities, RDP was not implemented. The offices were closed and subsequently replaced by a more “business friendly” and fiscally conservative model (Aliber 2003; Bond 2000:7). In early 1996, in the midst of much public debate as to what the RDP meant for economic policy, the RDP offices were closed and the staff dispersed to various government departments (Aliber 2003). Those opposed to GEAR were surprised by this shift in programme focus and wondered how the government would tackle the country’s problems of unemployment and poverty, using this inappropriate approach (Weideman 2004:9).

The introduction of GEAR totally overshadowed the RDP as the central economic programme of the government (Aliber 2003; Hargreaves & Meer 2000). The introduction of GEAR to replace the RDP reinforced government’s emphasis on fiscal discipline and export promotion (Weideman 2004). It is often said it is no coincidence that the word ‘redistribution’ is at the end of the acronym. GEAR is concerned mainly with economic growth and it was not surprising that it was warmly received and supported by business in South Africa. According to Bond (2000), critics of GEAR accused government of reneging on its promises of a people-driven process for service delivery. The move was labelled a “neo-liberal sell-out” (Bond 2000). Many scholars and critics ascribe problems in land reform and rural development to government’s abandonment of a more radical approach to social transformation (represented by the RDP), in favour of a more liberal, market-oriented approach (represented by GEAR) advocated by the World Bank (Bond 2000; Rangan & Gilmartin 2002). It was against this shift in strategies that the present land reform was implemented in South Africa.

LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA – GENDER ASPECTS

Generally, South Africa has reflected an awareness of a broad trend of issues of gender in land reform, especially among populists, Marxist and feminist writers, such as Bernstein (2003); Bernstein (2004); May (2000); Hargreaves and Meer (2000); Walker (1997); Walker (2003) and Hall (2007). Policies adopted by the ANC led government “outlined a strong commitment to gender and human rights in its approach to development” (Rangan & Gilmartin 2002:634). The state is legally committed to promoting and fulfilling the democratic rights of everyone which are set out in the Bill of Rights in the Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996. This has been seen as committing the state to promoting a “gender perspective”, embedded in all its programmes and policies (Hargreaves & Meer 2000). South Africa has also signed various declarations and conventions the aim of which was to promote women’s advancement (Rangan & Gilmartin 2002:634; Walker 2003).

In April 1997, South Africa’s Department of Land Affairs (DLA) approved a Land Reform and Gender Policy document (LRG Policy 1997b) aimed at creating an enabling environment for a gender-sensitive land reform (DLA 1998:13; Walker 2003). The document committed the Department to implementing a set of guiding principles to actively promote the principle of gender equity in land reform (Walker 2003).

The principles “included mechanisms for ensuring women’s full participation in decision making; communication strategies; gender sensitive methodologies in project planning; legislative reform; training; collaboration with NGOs and government structures and compliance with international commitments such as the 1995 ‘“Beijing Platform for Action”’ and the Convention on the Elimination of all Forms of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) which South Africa had re-ratified in 1995” (Walker 2003:123).

The approval of the gender policy document coincided with government’s formal adoption of its framework for land reform, the White Paper on South African Land Policy (Walker 2003). The White Paper endorsed gender equity as a key outcome to be achieved through the targeting of women as beneficiaries (DLA 1998:17). However, it is argued that, in practice there appears to have been very little advancement of gender rights and land reform in South Africa (Walker 2003:123; Rangan & Gilmartin 2002). Walker (2003) and Turner and Ibsen (2000) give reasons why gender equity in South Africa’s land reform has failed and among these are inconsistencies in the interpretations of gender equity and the lack of clarity on how women should be identified as beneficiaries of land reform.

There appears to be no connection between what is spelt out in formal policy documents and the treatment of gender issues in practice (Walker 2003:12). This is one of the thrusts of the thesis. The concern here is why gender equity has operated at the level of policy but not at the level of practice. To what extent has the DLA engaged with rural women? To do this, I will use the experience of Daggakraal during the first phase of land reform and argue that the current phase has not made it better for land reform beneficiaries, particularly women beneficiaries, either. Land reform has noble intentions and these are aimed at ushering in a just, productive society as envisaged in the White Paper on South Africa Land Policy (South Africa 1997a; Walker 2003). It has been viewed as a catalyst for altering unequal rural gender relations. However, for land reform to succeed as a catalyst for transforming gender relations in the countryside as Walker (2003) suggests, means there is a need to challenge the unequal gender relations that are embedded in the mind-sets of people living in the countryside.

The first phase of land reform in South Africa 1993 – 1999

The major aim of land reform under the Settlement and Land Acquisition Grant (SLAG) was to redress the injustices of colonialism and apartheid which had resulted in a skewed distribution of land where white South Africans, who represented about ten per cent of the population, owned about eighty-seven per cent of the land (South Africa 1997a; Mutangara 2007). In addition, land reform was intended to address extreme conditions of rural poverty in the countryside where the majority of South Africa’s poor lived, and to address the aspirations of women, in particular (Walker 2003; Cross & Friedman 1997). The land reform programme has three components and these are land redistribution, land restitution and land tenure reform. Land redistribution is aimed at transforming the skewed pattern of land ownership in the countryside and redressing the rural imbalance in land holding. Land restitution is aimed at addressing the restoration of historical rights in land for victims of forced removals and dispossessions. Land tenure reform is intended to secure and extend tenure rights for victims of forced removals and dispossession (Davis, Horn & Govender-Van Wyk 2004:6).

The first phase of land reform that emerged from the negotiated settlement and policy debates in the 1990s attempted to highlight a strong commitment to the goals of social justice within the principles of market-led land reform (Walker 2003). The task of the Department of Land Affairs (DLA) was to meet the expectations of land reform among the newly enfranchised majority; to draft and guide through an unfamiliar parliamentary process the legislation to achieve this; and to develop the institutional structures and operating systems to achieve its work. All of this had to be undertaken within the unsettled political transition with a limited budget and with a small core of new recruits (Walker 2003). At the time, the DLA worked within an isolated environment where there was no proper coordination between provincial and local governments (Hall 2007; Walker 2003:114). The purpose of the land redistribution programme was to provide the poor with access to land for residential and productive purposes in order to improve their quality of life and income (South Africa 1997a). It was to be realised through a market-assisted programme in which the state would support those wanting to acquire land, “willing buyers”, from those willing to sell their land, “willing sellers” (Lahiff 2007; Mearns 2011).

The Settlement and Land Acquisition Grant (SLAG) programme was introduced as a pilot programme in 1995 and in designated “pilot districts” in each province, while systems and procedures were developed and new offices set up (Walker 2003; Turner & Ibsen 2000). Utilising a state grant package, eligible households could purchase land on the market, assisted by the DLA or an NGO, and any balance of the grant remaining available was used for development of the land purchased (Davis et al 2004:6; Walker 2003). Because of the high cost of the land relative to the grant, most projects involved groups pooling their grants to buy land jointly, either as CPA or Trusts or Equity Schemes, as discussed elsewhere in this thesis (Bradstock 2005; Hall 2007). In most cases, strong historical ties held groups together, as did economic and social considerations (Hall 2007).

The projects focused primarily on resettlement and very little attention was given to economic development and this became a regular complaint of land reform critics in the country, especially those in the commercial farming sector (Levin 2000; Walker 2003). However, over time the DLA put more emphasis on smaller projects and ecological sustainability (an important step in that gender aspects were pushed to the background) (Levin 2000:68). For the period 1999, going into 2000, a Quality of Life Report commissioned by the DLA was cautiously positive about the achievements to date and among these was the target to reach the poorest of the poor, even on a very limited scale (DLA 2000). Most importantly, the study concluded that a “properly structured land reform programme has considerable potential for productive development and poverty eradication” (DLA 2000). By the end of 1999, redistribution efforts had transferred only 1.13 per cent of agricultural land to black ownership, and women accounted for 47 per cent of the 78 758 beneficiaries listed in the national database in June 2000 and this total included mainly joint male and female households, and not women as a distinct category (Walker 2003:114).

Although women were represented at project committee levels in some projects, male-headed households had access to larger plot sizes, on average, and female-headed households were less likely to use their plots for agricultural purposes (DLA 2000:26; Walker 2003). This assertion supports this study’s argument that the major problem is the fact that the concept of the household was not unpacked when the land reform policy was conceptualised and formulated. For this reason, the study will, among other things, serve as a window on gender relations in the countryside.

The second phase of land reform in South Africa

The late 1999s and early 2000s, when President Thabo Mbeki came into power and reshuffled the DLA, was a period marked by major shifts in the national policy framework that stressed the importance of agricultural productivity and the need for an African commercial farming sector (Jacobs 2010:173). During this period, a moratorium was placed on all existing projects pending a policy review and, significantly, income was dropped as a criterion for eligibility for land reform grants (Hall 2007; Jacobs 2010). This made it possible for wealthier black people to apply for grants under this new programme, the Land Redistribution for Agricultural Development Programme (LRAD) (Jacobs 2010). During this period, new senior management was appointed by the new Minister of Agriculture and Land Affairs. All of the above led to institutional paralysis because officials on the ground could not get proper directives from the new management who in turn were unable to provide the needed direction on the ground until a new policy document was published. This state of affairs effectively stifled operations on the ground (Hall 2007; Walker 2003). The new policy document, the Land Redistribution and Agricultural Development policy (LRAD), was finally published in 2000 and officials on the ground then had direction as to how to implement the programme (Walker 2003:121).

The aim of the new programme (LRAD) was to transfer 30 per cent of agricultural land from white to black ownership over 15 years and to revamp the earlier grant system to support agricultural initiatives (Walker 2003:125). Unlike in the earlier programme, in this phase grants are awarded to eligible individuals, as opposed to households, with grants ranging from R20 000 to R100 000 (DLA 2000:5). All members of disadvantaged groups are eligible, provided they make a contribution in cash or kind and use the grant for agricultural purposes and not for housing resettlement, as was the case in the earlier phase (Walker 2003:121). This is evidently a significant departure from the market-led and World Bank (WB) welfare proposals of providing a safety net for the poor, as well as an outright base grant.

Some gender activists have argued that the new shift from household to individual has opened up possibilities for women to own land and acquire land rights that are independent of the family and male control (Cross & Hornby 2002:55; Walker 2003). These land rights, however, mean that only the wealthier sections of black farmers, which include men and women, will be able to acquire land rights, to the exclusion of poor women and men in the countryside (Walker 2003). In essence, this means that although LRAD has noble gender specific targets, it is only wealthier women who will access the grant under this programme. For this reason, the problem of gender will remain unresolved (Rangan & Gilmartin 2002). There are valid fears that this programme will end up benefitting women in strategic positions only and that women who are poor may only enter the programme with the support of a male relative and this is a step backward from gender equity (Cross & Hornby 2002:55). It is hoped that recommendations emanating from this thesis will shed light on how this process and others on land reform could best address the gender aspects in South Africa.

As a result of prevailing unequal power relations in the countryside, as they affect the economic and social standing of most rural women, it is clear that only the better-off and educated women are likely to benefit from the new opportunities (Walker 2003). This programme is an ambitious one, implying a dramatic increase in budget allocation for the DLA, in staff capacity and general support for land reform at various levels of government. However, budget allocations for redistribution and tenure reform have not increased but declined from R421.9 million in 2001/2 to R339.5 million in 2003/4 (Walker 2003:125).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DECLARATION

DEDICATION

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ABSTRACT

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

CHAPTER 1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 BACKGROUND TO THE STUDY

1.2 THE LAND QUESTION IN AFRICA

1.3 BACKGROUND TO SOUTH AFRICA’S LAND ISSUES

1.4 WOMEN AND LAND RIGHTS

1.5 PROBLEM STATEMENT

1.6 THEORETICAL BASE

1.7 THE AIM AND OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY

1.8 THE DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA

1.9 MOTIVATION FOR THE STUDY

1.10 METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES

1.11 SCOPE OF THE RESEARCH AND METHODOLOGY

1.12 LIMITATIONS OF THE STUDY

1.13 ORGANISATION OF THE STUDY

CHAPTER 2 LITERATURE REVIEW AND THEORETICAL FOUNDATIONS OF THE STUDY

2.1 INTRODUCTION

2.2 THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON LAND REFORM, GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT

2.3 REASONS FOR LAND REFORM

2.4 MODERNISATION THEORY AND THE WORLD BANK: THE EMERGENCE OF GENDERED APPROACHES TO DEVELOPMENT

2.5 THEORETICAL BASE DEFINITION OF CONCEPTS

2.6 GENDER ANALYSIS – CONCEPTUAL PROBLEMS

2.7 GENDER AND LAND REFORM PROCESSES

2.8 THE IMPORTANCE OF LAND

2.9 THEORETICAL PERSPECTIVES ON LAND REFORM, GENDER AND DEVELOPMENT: A SUMMARY

2.10 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 3 THE LEGISLATIVE AND INSTITUTIONAL FRAMEWORK FOR LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA

3.1 INTRODUCTION

3.2 THE LAND QUESTION IN THE THIRD WORLD

3.3 BACKGROUND TO LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA

3.4 LAND REFORM IN SOUTH AFRICA – GENDER ASPECTS

3.5 LAND TENURE REFORM.

3.6 THE ROLE OF THE WORLD BANK IN SHAPING LAND REFORM POLICY IN SOUTH AFRICA

3.7 PROVISION OF LAND AND ASSISTANCE ACT 1993.

3.8 THE LAND REFORM (LABOUR TENANTS ACT) (1996)

3.9 EXTENSION OF SECURITY OF TENURE 1997 AND AMENDMENTS OF 2001

3.10 COMMUNITY PROPERTY ASSOCIATIONS ACT 28 of 1996 (CPA)

3.11 THE WHITE PAPER ON SOUTH AFRICAN LAND POLICY 1997

3.12 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 4 DESCRIPTION OF THE STUDY AREA AND RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

4.1 INTRODUCTION

4.2 THE GENDER ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK (GAF)

4.3 RESEARCH QUESTIONS

4.4 RESEARCH METHODS AND DATA ANALYSIS

4.5 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND TO THE RESEARCH AREA

4.6 RESEARCH METHODOLOGY AND METHODOLOGICAL CHALLENGES

4.7 THE LINK BETWEEN PARTICIPATORY RESEARCH METHODOLOGIES AND THE GENDER ANALYSIS FRAMEWORK

4.8 ETHICAL PRINCIPLES AND DATA ANALYSIS

4.9 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 5 RESEARCH FINDINGS

5.1 INTRODUCTION

5.2 SECONDARY DATA ANALYSIS

5.3 ANALYSIS OF PRIMARY DATA

5.4 CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 6 CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.1 INTRODUCTION

6.2 KEY RESEARCH FINDINGS

6.3 CONCLUSION

6.4 RECOMMENDATIONS AND FUTURE RESEARCH

BIBLIOGRAPHY

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT