Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

This chapter of the thesis presents the relevant theoretical framework to clarify and support the topic of this thesis. First, the concepts of Talent Management and talent are explained, as there are ambiguities around these concepts, previous research and frameworks are presented to give an overview of the concepts. The alignment of Talent Management and strategy is further explained. These concepts are the foundation for the development of a conceptual framework presented at the end of this chapter. This framework is specifically developed for the purpose of this thesis and is later on used as the basis for the analysis.

Talent Management

The concept of Talent Management suffers from both theoretical and practical limitations, as the terminology does not have stable and clear theoretical support in the existing literature (e.g. Lewis & Heckman, 2006; Dries, 2013; Thunnissen et al., 2013; Bolander et al., 2014; Sparrow, Scullion & Tarique, 2014) . Throughout the research of previous literature, the definitions of Talent Management vary, for most part the differences are on the understanding of how broadly Talent Management is defined. Lewis and Heckman (2006) identified three streams of understanding what Talent Management is. The first stream explains Talent Management as a substitute for Human Resources, the second through a focus on the development of talent pools, and third explains Talent Management as management of talents, i.e. employee performance (ibid.). Collings and Mellahi (2009) add a fourth stream to this list, which emphasises the identification of key positions, thus the focus is on positions rather than talented individuals.

As there is much ambiguity around the definition of Talent Management, Dries (2013) argues this to leave room for “interpretative flexibility”, which can result in inconsistencies between the organisation’s intentions and practice. Furthermore, Bolander et al. (2014) argue there to be an evident lack of rigorous research that would pay more close attention to the actual organizational practices to carry out Talent Management activities. Therefore, following the third stream identified by Lewis and Heckman (2006), and outlining a definition of Talent Management this thesis follows, Cappelli and Keller (2014) clarify that Talent Management implies having a set of established practices that aim at getting the right person in the right job at the right time. To support this, many researchers have adopted a similar way of defining Talent Management as a type of process or a set of systematic activities (e.g. Ashton & Morton, 2005; Silzer & Dowell, 2010; Armstrong, 2011; Bethke -Langenegger, Mahler & Staffelbach, 2011; Dessler, 2013, p.130; Meyers & van Woerkom, 2014; Sparrow et al., 2014). For example, Meyers and van Woerkom (2014) define Talent Management as “the systematic utilization of Human Resource Management (HRM) activities to attract, identify, develop, and retain individuals who are considered to be ‘talented’” (p.192). However, the practices can be outlined in various ways, as can be the definition of ‘talented’ (Cappelli & Keller, 2014; Meyers & van Woerkom, 2014), which will be explained more in detail in section 2.2 View on Talent.

Talent Management Practices and Processes

Talent Management literature has been known to emphasise the best practice approach, which entails exemplifying certain practices that are considered successful and thus should be followed (Stahl, Björkman, Farndale, Morris, Paauwe, Stiles, Trevor & Wright, 2012). However, more recent research shows that there should rather be a best fit approach, which demands a more context specific approach to designing these Talent Management practices (Pfeffer, 2001; Boudreau & Ramstad, 2005; Collings & Mellahi, 2009; Sparrow, Hird & Balain, 2011; Vaiman et al., 2012; Dries, 2013; Festing et al., 2013; Bolander et al., 2014). “Practices are only ‘best’ in the context for which they were designed” (Stahl et al., 2012, p.26). Albeit, the most dominant practices in Talent Management can be identified to be related to identification, recruitment, training and development, staffing and succession planning and retention management of talents (Dries & Pepermans, 2008; Collings & Mellahi, 2009; Armstrong, 2011; Stahl et al., 2012; Thunnissen et al., 2013; Bolander et al., 2014). However, Sparrow et al. (2014) argue that formulating Talent Management systems can be challenging since there are many options on how to combine different policies and practices available. As Garrow and Hirsh (2008) emphasise, Talent Management is a matter of best fit, i.e. fit with strategic objectives, organizational culture, other HR practices and policies, and organizational capacity.

To gain a better understanding of what type of practices are available regarding Talent Management, Stahl et al. (2012) present some important elements, i.e. best principles a successful Talent Management process should include. Thus, a successful Talent Management should have its main focus on elements such as recruitment, staffing and succession planning, training and development, and retention management (ibid.). According Dries and Pepermans (2008), the four main aspects of Talent Management are identification, training and development, succession planning, and retention management. Hence, combining these two perspectives to gain a broader understanding, the most dominant practices in Talent Management can be concluded to be identification, recruitment, training and development, staffing and succession planning and retention management (Dries & Pepermans, 2008; Stahl et al., 2012). This is to argue that Talent Management is a system or a set of practices and activities that are complete and interrelated (Thunnissen et al., 2013) . Thus, the exemplification of certain practices is to be understood as a guiding principle as Stahl et al. (2012) stated, not only as simply descriptive of practices based on previously found success stories, as Sparrow et al. (2014) on the contrary emphasise. Best practices approach, such as this would entail practices that can be copied and duplicated and thus can cause challenges for organizations and steer away from being strategically important differentiation factor for organisations (Ashton & Morton, 2005; Stahl et al., 2012). Cappelli and Keller (2014) thus emphasise Talent Management to imply having a set of established practices aiming at getting the right person in the right job at the right time.

View on Talent

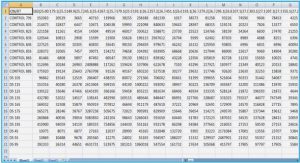

To be able to fully understand the definition of Talent Management, it is necessary also to understand the way talent is characterised (Dries, 2013; Bolander et al., 2014). Huselid, Becker and Beatty (2009, p.7) refer to talent as a strategic asset since it represents something that is valuable, rare, inimitable and non -substitutable, and enables the implementation of value creating strategies and achievement of sustainable competitive advantage. Even though, this definition gives a basis for understanding how talent can be perceived from the resource-based view, Bolander et al. (2014) argue that the nature of talent is not as self evident as the aforementioned characteristics entail and varies widely in the Talent Management literature. Gallardo-Gallardo, Dries and González-Cruz (2013) claim that in many previous studies, talent is only recognised as an underlying construct, i.e. taken for granted and not explicitly defined. Ulrich (2011) further states that talent can mean whatever the academic researcher or a business practitioner wants it to mean. Table 1 below exemplifies the discrepancies and variance in the definitions of talent within the academic literature.

From the different discussions regarding talent, Dries (2013) identifies five main tensions for understanding talent in the current literature. These are object versus subject, inclusive versus exclusive, innate versus acquired, input versus output and transferable versus context dependent (ibid.). These tensions are considered as choices on a continuum, meaning that the view on talent is not necessarily either or question between the tensions, as companies tend to have a view on talent that combines these tensions in different ways (Sparrow et al., 2011; Stahl et al., 2012; Dries, 2013).

Object versus subject perspective refers to the discussion about who is talent (Dries, 2013). Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2013) have been researching this tension more specifically and identify these to be the two main dimensions of how talent can be viewed. Object perspective refers to the characteristics of people, considering for example their natural abilities, commitment or fit as talent, whereas subject perspective refers to talent as people (ibid.). Dries (2013) states that this distinction in practice is difficult to make since characteristics of a person cannot be independent from the person as a whole. On the same note, Bolander et al. (2014) found there to be a subject perspective in all of the discovered approaches to Talent Management.

Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2013) and Thunnissen et al. (2013) clarify the subject approach to further include the second tension of Dries (2013), inclusive versus exclusive perspective. The second tension on inclusive versus exclusive perspective stems from the discussion of how prevalent talent is in the population, for example the organisation (ibid.). The inclusive versus exclusive tension is claimed to be the main debate on the view on talent (Lewis & Heckman, 2006; Tansley, 2011). Inclusive perspective has a focus on all the employees as talents, whereas the exclusive perspective has a focus only on a selected group of employees (Thunnissen et al., 2013). Lewis and Heckman (2006) exemplify the exclusive approach to be about classifying employees based on their performance. Malik and Singh (2014) further explain that organisations can implement so called “high potential” (HiPo) programs to identify, develop and retain the most talented employees, i.e. a small group of employees. This is the basis for workforce differentiation that drives the exclusive approach. However, this approach is criticised for not taking into consideration those employees who are not in the group of the talented employees. Thus, the inclusive approach emphasises that the role of the HR function should be to manage everyone to reach high performance and hence to be regarded as talents. (Cappelli & Keller, 2014; Malik & Singh, 2014) According to Sparrow et al. (2011), the exclusive perspective seems to be more prominent, although Stahl et al. (2012) argue the combination of both approaches to be used more in particular in the global Talent Management context because it allows to consider differentiation and avoids issues of whether some employees are more valuable than others.

Innate versus acquired perspective is the third tension and debates on whether talent is something that can be learned or taught, embarking on the nature -nurture debate. Innate perspective understands talent to be within individuals and thus focuses on the selection and identification of talent, whereas the acquired perspective focuses on the development of talent as it is considered to be something that can be learned or taught. (Dries, 2013) Meyers et al. (2013) have studied this tension more in detail and suggest that when deciding on this perspective, there should be a consideration on the type of talent that is needed, prior experiences, the labour market supply of talent, labour market regulations, as well as certain strategic considerations should be noted.

Furthermore, Tansley (2011) found this tension to be culture dependent, as the linguistic comparison of talent shows differences in how the term is perceived.

The fourth tension on input versus output perspectives entails the question of whether talent is more about ability or motivation (Dries, 2013). “Input perspectives on talent imply a focus on effort, motivation, ambition, and career orientation in assessments of talent. Output perspectives on talent, on the other hand, imply an assessment focus on output, performance, achievements, and results.“ (ibid., p.280) Ability, i.e. the output, tends to be the sole focus in most organisations (Church & Rotolo, 2013), and motivation aspect is yet to gain appreciation in the Talent Management research and practices (Dries, 2013). However, motivation should be valued more as achievements attributed to motivation are valued more (at least within employees themselves) and motivation is an important part of avoiding employees or even leaders to be derailed from their high potential talent statuses (ibid.) .

Last, transferable versus context-dependent perspective on talent refers to the discussion surrounding the extent to which talent emerges regardless of the context, i.e. to what extent can talent be transferred without it losing its quality or whether it only emerges in a certain context. This approach is closely linked to the decisions organisations make on internal and external recruitment. (Dries, 2013) There are not much research yet done on this particular tension identified by Dries (2013), however, the best fit approach discussed by many researchers and the context-specific studies conducted by Bolander et al. (2014), Festing et al. (2013), Meyers et al. (2013), among others, seem to emphasise the importance of the specific context. Again, these tensions can be understood as part of a continuum and one extreme over the other is not necessarily the ultimate view on talent (Dries, 2013).

Dries (2013) stresses that these perspectives and tensions are not fully independent from each other. Bolander et al. (2014) claim that previous frameworks and typologies surrounding Talent Management often have an unbalanced emphasis on one aspect over the other, which can result in obscuring the realities of the diverse ways of viewing talent in practice. Furthermore, Boudreau and Ramstad (2005) claim that no single perspective on talent can be objectively stated to be the best. Garrow and Hirsh (2008) state Talent Management to be about the best fit. Tansley (2011) further claims that talent is specific to an organisation, as the definition is influenced by the industry and the nature of the internal work dynamic. Thus, Dries (2013), alongside majority of the more current researchers, emphasise yet again the best fit approach and leave to define talent in more detail. Based on the argumentation above, the view on talent in this thesis will be determined on a somewhat general level, in accordance with Huselid et al. (2009, p.7), referring to talent as a strategic asset, representing something valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable, and enables the implementation of value creating strategies and achievement of sustainable competitive advantage. A more specific definition is not feasible for this thesis because a more narrow and simplistic view on talent would constrain the aspects of Talent Management and thus restrict further discussions and analysis.

Approaches to Talent Management

The discussion in the previous section about the different views on talent is important, as it has implications on how Talent Management is approached (Festing et al., 2013; Meyers et al., 2013; Bolander et al., 2014) Bolander et al. (2014) clarifies that quite recently, it has been emphasised in the academic research that Talent Management can be approached in different ways by different organisations. Festing et al. (2013) found that the differences can stem from the intensity of Talent Management initiatives. However, Bolander et al. (2014) found there to be more reasons why Talent Management looks so different in different organisations. These reasons relate to the orientation and focus of the Talent Management activities present. Therefore, Dries (2013) argues that the organisation’s position in the continuum of the different tensions mentioned earlier has implications for the design on the Talent Management practices decided to be conducted in the respective organisation. Meyers et al. (2013) further state that this entails variations in the emphasis organisations have on the specific Talent Management practices. For instance, Dries (2013) exemplifies this by questioning whether the focus of Talent Management is highly placed on the identification of talents or rather on the development activities. Reflecting back on the best fit approach, different approaches to Talent Management can be equally feasible and can differ in many ways, no one approach is better than the other and each has its own advantages and disadvantages (ibid.).

However, the ambiguity around Talent Management is still apparent and Gallardo-Gallardo et al. (2013) claim the ongoing confusion about the meaning of talent in particular to be a hinder for the further development of more widely acknowledged Talent Management theories and practices. Bolander et al. (2014) embarked on bringing clarification to the view on talent and its impact to the approach Talent Management takes. The framework findings integrate theoretical insights from various stems of research, and can be used as a conceptual framework for identifying Talent Management types across organisations. Furthermore, the companies were Swedish, as opposed to the many US-based research done before, which enabled them to give a broader perspective on the view on talent as it was not contained by the more individualistic oriented culture of the US but considered in a more collectivistic culture, bringing new perspective on the view on talent (ibid.) . As mentioned before, this contributes to the understanding that nature of talent can vary between different organisations (Festing et al., 2013; Meyers et al., 2013; Bolander et al., 2014). Bolander et al. (2014) developed three approaches to Talent Management, namely humanistic approach, competitive approach and entrepreneurial approach . The view on talent in each of these approaches is based on the five tensions identified by Dries (2013) and the findings exemplify how these tensions on the nature of talent affects the construct of Talent Management (Bolander et al., 2014).

Humanistic approach considers each employee to have some kind of talent, as a result all employees are viewed as talented. Certain top performers possess a particular talent but other employees are considered to have some other types of talent. The humanistic approach is characterised by the idea that talent is developable rather than innate. Ability is part of talent, however, the interests and desires of the individual are more important. For instance, talent is seen as context-dependent to the extent that where a person is underperforming in one part of the organisation, that person might still be recognized as a talent in another setting. Organisations with a humanistic approach prioritize the effort of “making” talent, as outside talent recruitment can send a message that current employees are not good enough. Thus, development opportunities are extended to all employees regardless of professional background. In order to identify talent, regular talent reviews are conducted with the purpose to find the right placement for employees within the organisation. Through talking to people, assessments are made based on a holistic view on talent rather than through some explicit criteria. These assessments are conducted informally and are usually subjective, career paths are loosely defined and organised around the interests and desires of the individual. Once an employee has communicated how he/she wants to develop, it is then expected that management facilitates the development opportunities. (Bolander et al., 2014)

Competitive approach on the contrary identifies that only some of the employees hold abilities that outline them as talents. This identification sets them apart from their colleagues and thus is an important difference to pay attention to. This can be considered as an exclusive approach, as it identifies a small group of employees as “stars”, whose excellent performance and high potential set them apart from other employees. This approach further considers each employee to have an inborn capacity to reach a certain organisational level. Whereas ability and focus on past performance is seen as talent. According to these types of organisations a talent will be a talent regardless where placed, and there is a strong sense of competition for talent amongst those employers who support this type of view. Thereby, employers focus more on “buying” talent than “making” talent, in regards to “buying” talent, it is more common to have the lookout for hiring the best talent. The principal practice of the competitive approach is the talent identification process, more specifically identifying the talented few and admitting them to talent pools. All employees are placed and considered in a grid with axes of performance and potential. The axe of performance evaluates the progress of the current role and potential axe reflects the readiness for promotion and likeliness to succeed. Talent development within competitive approach is mainly program-based, by thus employees are nominated to exclusive programs designed to follow a clearly defined career path for leaders, specialists and project leaders. Employees in these types of programs are expected to advance vertically, implying high investments of time and energy from the organisation’s side. It is notable within the competitive approach that talent is transferable and presumably these organisations seek the same talents as their competitors. (Bolander et al., 2014)

Table of contents :

1 INTRODUCTION

1.1 Problem Description

1.2 Purpose & Research Question

1.3 Significance of the Research

1.4 Delimitations

1.5 Outline of the Thesis

2 THEORETICAL BACKGROUND

2.1 Talent Management

2.1.1 Talent Management Practices and Processes

2.2 View on Talent

2.3 Approaches to Talent Management

2.4 Strategy and Talent Management

2.4.1 Strategic Talent Management

2.4.2 Maturity of Talent Management

2.5 Summary and Framework for the Main Concepts

3 METHODOLOGY

3.1 Research Topic

3.2 Research Strategy

3.3 Research Design

3.4 Sample and Data Selection

3.5 Data Collection

3.5.1 Secondary Data

3.5.2 Primary Data

3.6 Data Analysis

3.7 Research Quality

3.8 Ethical Considerations

3.9 Limitations

4 EMPIRICAL FINDINGS

4.1 View on Talent

4.2 Approach to Talent Management

4.2.1 Talent Management Process

4.2.2 The Aim, Measures and Success of Talent Management

4.2.3 Challenges and Benefits of Talent Management

4.3 Development of Talent Management

4.4 Alignment of Talent Management to Strategy

5 ANALYSIS

5.1 Relationship of View on Talent and Talent Management

5.2 Relationship of Talent Management and Strategy

5.3 Relationship of Strategy and View on Talent

5.4 Application of Conceptual Framework and the Identification of Patterns

6 CONCLUSIONS

6.1 Managerial Implications

6.2 Suggestions for Future Research

7 REFERENCES

APPENDIX