Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Analysis

This chapter builds on the results and findings of the theoretical framework. By investigating the results and connecting them with each other, a deeper understanding of the relationship between cultural values and their effects on the UPB on SNSs is established. Regarding the quantitative data, the statistical analysis methods, as presented in chapter 3 (independent samples t-Test and Mann-Whitney U Test), facilitate the analysis. Regarding this, in order a relationship to be considered as statistically significant in this study, both the independent samples t-Test and Mann-Whitney U Test need to indicate a statistically significant relation-ship. Moreover, through a content analysis of the open-ended question, findings of both quantitative and qualitative nature are used complementary, resulting in a deeper understand-ing. This chapter is divided according to the five UPB on SNSs constructs.

Friends and Relationships on SNSs

As mentioned in section 2.4.4.1, Hofstede (2001) characterizes high masculinity cultures (such as Germany) as ego-oriented, while low masculinity cultures (such as Sweden) are ra-ther relationship-oriented. H1.1 builds on this by claiming that Swedes have more SNSs friends than Germans. Indeed, as Table 4.1 illustrates, the results seem to reflect that state-ment. In fact, the application of statistical significance tests revealed a statistically significant difference. Both the independent samples t-Test and the Mann-Whitney U Test confirmed this, and hereby H1.1 can be considered as true: Swedish SNS users have more SNS friends than German SNS users. In order to draw inferences from that about UPB on SNS, the real life relationship to these SNSs friends needs to be analyzed. H1.2 claims that Swedish SNS users have more close friends in their SNS friends list than German SNS users. Table 4.2 illustrates the same, however neither the independent samples t-Test nor the Mann-Whitney U Test could determine a statistically significant difference. As a consequence, H1.2 cannot be confirmed. On the other hand, H1.3 suggests that German SNS users have more strangers in their SNS friends list than Swedish SNS users. Interestingly, regarding this hypothesis, a statistically significant difference could be determined, however in the opposite direction: Swedish SNS users have more strangers in their SNS friends list than German SNS users. This proves H1.3 wrong. H1.3’s underlying argumentation, claiming that relationship-ori-ented cultures focus on close relationships, has to be considered as inappropriate. On the contrary, it seems that a culture’s relationship orientation increases the overall number of SNS friends, irrespective of the real life relationships to these virtual friends. Considering the remaining statements of this block, no statistically significant differences could be observed. According to the independent samples t-Test, there exists a significant difference in the number of SNS friends someone is in regular contact with in real life, with Germans revealing a higher number than Swedes. Investigating the same question with the Mann-Whitney U Test, however, does not end up in a statistically significant difference. Considering the last statement, relating to the number of friends someone has never met in real life, the Mann-Whitney U Test determines a significant difference, with Swedes revealing a higher number than Germans. According to the independent samples t-Test though, the difference is not statistically significant. The different test results can be ascribed to the dif-ferent figures that both tests are comparing. Additionally, considering German respondents, both statistical tests revealed significant dif-ferences in the number of Facebook friends between males and females. According to that, German males have more friends on Facebook than German females and German females are with a higher amount of their Facebook friends in regular contact in real life compared to German males. No significant differences could be found comparing genders among Swe-dish respondents. Both the observed differences in German genders and the similarities in Swedish genders strengthen Hofstede’s (2001) above-mentioned (section 2.4.4.1) definition of masculinity and femininity in which he describes masculinity as “a society in which social gender roles are clearly distinct […]. Femininity stands for a society in which social gender roles overlap” (Hofstede, 2001, p. 297). Altogether, two significant differences could be identified. Firstly, Swedish users have more friends on Facebook than Germans (= H1.1), and secondly, Swedes consider a higher amount of their Facebook friends as strangers in real life (≠ H1.3). According to that, it is assumed that having more SNS friends, with a higher amount of strangers within these friends, increases the probability of privacy threats. In fact, Poh (2012) claims: The more ‘friends’ [on Facebook] we have, the fewer our interactions are with most of them. You usually end up having only a few ‘friends’ […] [which] are also your close friends offline. The rest of your ‘friends’ on Facebook are obsolete, irrelevant, disconnected, and just random receivers of your updates. […] The issue here is the sharing of your information to people whom you don’t even know. […] The loss of your privacy through such voluntary sharing actually makes your position all the more vulnerable and you can’t do anything about it” (Poh, 2012). This becomes clear when considering the fact that, as mentioned in chapter 2, by default, each Facebook friend has full access to a person’s Facebook profile and hence to his or her personal information. The following section analyzes the results referring to German and Swedish respondents’ trust and confidence in both Facebook and other Facebook users.

Trust and Confidence on SNSs

This section is divided into two parts. The first part analyzes SNS users’ trust in SNS pro-viders and the second part their trust in other SNS members.

Trust in Facebook

As described in section 2.4.4.2, there exist substantial differences in the attitudes that cul-tures, characterized by a high uncertainty avoidance (such as Germany), and cultures, with a low uncertainty avoidance (such as Sweden), have toward other entities. Hofstede’s (2001) stated real life examples show that low uncertainty avoidance cultures are optimistic toward others, which cannot be said for high uncertainty avoidance cultures. H2 builds on that and links these attitudes to UPB on SNS by claiming that Swedish SNS users have more trust and confidence in SNS providers than German SNS users. Indeed, the results illustrated in Figure 4.1 show that Swedes share a more optimistic attitude toward Facebook. Both the independent samples t-Test and the Mann-Whitney U Test revealed that, in six out of seven statements, the differences between the German and Swedish respondents’ agreements were statistically significant. The difference to the second statement, claiming that Facebook made good-faith efforts to address most members concerns, could not be proven to be statistically significant. The tests show that Swedes, compared to Germans, consider Facebook as more open and receptive to the needs of its members. They also, to a higher extent, perceive Fa-cebook honest in its dealings with them. However, regarding the latter statement, the mean values of both Germans and Swedes are below four, indicating a relative low overall trust. Furthermore, Swedes share the opinion that Facebook keeps its commitments to its mem-bers. Germans rather perceive the opposite. Regarding the statement which claims that Fa-cebook is trustworthy, both nationalities indicate an agreement below four. However, Swe-dish respondents’ agreement is higher than the one of German respondents. The same ap-plies to the last statement concerning Facebook’s honesty when it comes to the collection and use of personal information. Interestingly, same as in the previous section, both applied statistical tests determined signif-icant differences between the genders of German respondents. Their responses significantly differ at six out of seven statements, with females always agreeing to a higher extent, thus revealing higher trust and confidence. On the other hand, the responses of Swedish genders only differ at one statement significantly, with females also indicating higher trust. This again highlights the gap between genders which increases with the masculinity of a culture (Hofstede, 2001). Altogether, all the above-mentioned significant differences reveal that Swedish SNS users actually have more trust and confidence in SNS providers compared to German SNS users. Here it is important to consider that this statement refers to a comparison. Even though Swedish respondents also reveal a disagreement to some statements, their overall agreement always exceeds the German respondents’ agreement. H2 can therefore be confirmed: Swe-dish SNS users have more trust and confidence in SNS providers than German SNS users.

Trust in other Facebook Users

As mentioned in section 2.4.4.2, cultures characterized by a high uncertainty avoidance (such as Germany) are rather pessimistic toward other people, even including family members. On the other hand, members of cultures with a low uncertainty avoidance (such as Swedes) share the opinion that most people can be trusted. This is the underlying argumentation for H3 which states that Swedish SNS users have more trust in other SNS members than German SNS users. According to the independent samples t-Test and the Mann-Whitney U Test, the responses to the first five statements, as presented in Figure 4.2, show statistically significant differences. These statements strengthen H3, as Swedes indicate higher agreements to each of these, implying higher trust. Only the responses to the last statement, claiming that Face-book users are open and delicate to each other, do not significantly differ between Germans and Swedes. The tests prove that Swedes, compared to Germans, rather share the opinion that other Facebook users would not misuse their sincerity on Facebook. Furthermore, Ger-mans tend to think that other Facebook users would embarrass them for provided infor-mation on Facebook and could use this information against them or in a wrong way. Swedes, on the other hand, have more trust in other Facebook users and assume the opposite. Be-sides, Swedes perceive other Facebook users as trustworthy, while Germans are rather careful toward them. Interestingly, all responses of Germans reach a mean value below four, while all Swedish responses, except the last one, end up in a mean value above four. As a conse-quence, H3 can be confirmed: Swedish SNS users have more trust in other SNS members than German SNS users. The analyses of the results, as conducted in the previous and this section, clearly confirm Hofstede’s (2001) characterization and prove that the respective cultural values also have an influence on trust on SNSs. Whether the users’ trust and confidence on SNSs influence their privacy concerns, as claimed by (Pavlou, 2003), is analyzed in the following section.

Privacy Concerns

As illustrated in section 2.4.1 and 2.4.3, the extent to which individuals are concerned about privacy differs from culture to culture. While some authors found a negative relation between uncertainty avoidance and privacy concerns (Milberg et al., 2000), others could not determine any relation at all (Bellman et al., 2004). H4, though, based its assertion on the assumption that cultures with more trust in other entities consequently reveal lower privacy concerns. According to that, H4 claims that German SNS users have higher privacy concerns on SNSs than Swedish SNS users. Indeed, regarding Figure 4.3, it seems that uncertainty avoidance has a positive effect on privacy concerns of individuals. To three out of four statements, German respondents, as members of a high uncertainty avoidance culture, indicated a higher agreement than Swedish respondents, thus higher privacy concerns. Only to the statement, referring to the concerns that submitted information on Facebook could be misinterpreted, Swedes agreed to a higher extent. The independent samples t-Test and the Mann-Whitney U Test only determined a significant relationship at two statements. According to that, Germans are more concerned that their information submitted on Facebook could be used in a way they did not foresee and they also rather share the opinion that this information could be continuously spied on (by someone unintended). Also in this case, all responses of both Germans and Swedes reach mean values above four, meaning that both cultures have relatively high privacy concerns. By regarding Figure 4.4, the differences become more obvious. At each of the 21 elements, Germans are more concerned that information could be visible by everybody. Furthermore, both statistical tests indicate statistically significant differences in 20 out 21 elements. Only the responses to the personal information “Gender” did not significantly differ between Germans and Swedes. As a consequence, H4 can be confirmed: German SNS users have higher privacy concerns on SNSs than Swedish SNS users. As mentioned in section 2.4.4.2, users are concerned about strangers accessing their personal information, yet, they still provide it on their profiles (Cho, 2010). This section has high-lighted SNS users’ concerns and the following analyzes whether these concerns correspond to the actual behavior by investigating SNS users’ self-disclosure.

Self-Disclosure on SNSs

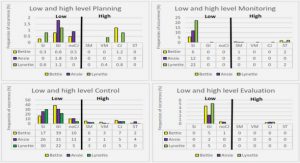

As presented in section 2.4.2, the usage behavior on SNSs, including self-disclosure, differs from culture to culture. While some cultures tend to keep their public profile anonymous, others frequently exhibit self-disclosure. The construct “Self-Disclosure on SNSs” is ana-lyzed based on two question blocks. Block one (Figure 4.5) consists of six statements. To be able to extract valuable information, resulting into valid conclusions, the significance levels of the differences in the mean values between the two groups (nationalities), German and Swedish respondents, need to be determined first. Independent samples t-Tests show a sig-nificant difference in statement one (“I have a detailed/comprehensive profile on Face-book.”), two (“Personal information I publish on Facebook always represents the truth.”), four (“My profile tells a lot about me.”), and six (“From my Facebook profile it would be easy to understand what person I am.”). Statement three (“I always find time to keep my profile up-to-date.”) and five (“From my Facebook profile it would be easy to find out my preferences in music, movies or books.”) show no significant difference. The Mann-Whitney U Tests confirm these significance levels. The same tests are processed for the findings of Figure 4.6. According to the calculated independent samples t-Tests, the following infor-mation fields of show statistically significant differences: Name, E-Mail, Phone number, Employer, Education, Hometown, Location (country), Location (city), Location (street), Profile Picture, Relationship status, Biography, Religion, Photos, and Videos. The fields Gen-der, Nationality, Birth date, and Interests do not show significant differences in their mean values of both nationalities. The Mann-Whitney U test confirms these findings. The construct is investigated through H5, claiming that German SNS users reveal a lower self-disclosure on SNSs than Swedish SNS users. Based on the previously presented defini-tion of a user’s self-disclosure (“[A user’s self-disclosure] reflects the amount of information shared on a user’s profile as well as in the process of communication with others” (Krasnova Veltri, 2010, p. 2)), the statistically significant statements of and Table 4.3 substantiate H5 and prove it to be right. Indeed, German respondents show a lower tendency to have a detailed/comprehensive profile than Swedish respondents. With only 70% of the German respondents (compared to 97% of the Swedish) publishing their valid name, they do not only publish less information, but more invalid data too. In fact, every single information field asked about is less often published validly by Germans than by Swedes. This observation matches the results retrieved from the statement, claiming that published personal infor-mation represents the truth and tells a lot about them, to which less German than Swedish respondents agreed upon. These findings are rooted in the weak trust relationship between German users and SNS providers (H2) and a generally high distrust against other SNS users (H3).It should be noted though, that although the German respondents reveal a lower self-disclo-sure on SNSs than Swedes, this does not imply that Swedes can be categorized as having a per se high self-disclosure. Such propositions need to be proven right or wrong by comparing a higher quantity of nationalities, to see how a single culture fits into the bigger picture.Which impacts the acceptance of the H5 has on the actual perception and adaption of avail-able privacy settings is investigated in the following section.

Control over Personal Information on SNSs

The next construct to be analyzed is “Control over Personal Information on SNSs”. The construct is investigated through two hypotheses, H6.1: German SNS users perceive less given control over personal information on SNSs than Swedish SNS users, and H6.2: Ger-man SNS users adapt more privacy settings on SNSs than Swedish SNS users.

Perception of Provided Control

The perception of provided control is investigated based on one question block and one open-ended question. The statements of the question block can be found in Figure 4.7. The independent samples t-Tests show significant differences in the mean values between the two nationalities for the statements: Facebook provides me enough control over the information I provide on Facebook (e.g. in my profile, on the Wall etc.); Facebook provides me enough control over how and in what case the information I provide can be used; and Facebook provides me enough control over who can collect and use the information I provide. However, statements four (“Facebook provides me enough control over who can view my information on Facebook.”) and five (“Facebook provides me enough control over the actions of other users.”) show no statistically significant differences. The Mann-Whitney U test confirms these findings. H6.1 conjectures that German SNS users perceive their given control over personal infor-mation as less sufficient on SNSs than Swedish SNS users. This hypothesis is based on the assumption that, as a result of their high uncertainty avoidance, German users show stronger control needs over their private information than Swedish users. In fact, the results in con-firm this assumption. To all statements to which the differences in responses are statistically significant, German respondents state lower agreements. Based on these findings, H6.1 can be confirmed: German SNS users perceive their given control over personal information on SNSs as less sufficient than Swedish SNS users. In this regard, the answers of the open-ended question reveal interesting insights into peo-ple’s thoughts. For the open-ended question, asking for the respondents’ opinion about why the given control over personal information on Facebook is insufficient, a conventional con-tent analysis is done. By analyzing the answers, six categories of responses could be identified: accessibility/usability of settings, (2), insufficient control provided for publishing (3), in-sufficient control provided over other users, (4) changing nature of Facebook, (5) inability to delete account/data permanently, and (6) trust in Facebook/Facebook partners. Each comment is assigned to one or more categories, which means that the accumulated sum of the percentages exceeds 100%. A collection of all answers is attached in Appendix C and divided in German and Swedish responses.shows the distribution of comments within the five categories; e.g. 22.22% of the Germans and 41.94% of the Swedish respondents’ comments are assigned to category one. The numbers next to the percentages show the ranks, used to represent an ascending order of the categories’ frequency distribution. The majority of the German respondents indicate problems about the sufficiency of provided control settings for publishing personal infor-mation (ID2), whereas most of the Swedish responses are assigned to problems concerning the accessibility or usability of provided settings (ID1). Both nationalities express high con-cerns about the trust in Facebook and its partners (ID6) and evaluate ID4 and ID5 as the least important. Though, 7.41% of the comments of German respondents state concerns about category ID4, whereas not even one Swedish participant expresses such concerns about the inability to delete the user account or data permanently on Facebook. Some com-ments of each category are presented below (grammatical/spelling mistakes have been cor-rected).Several respondents state concerns about the accessibility and usability of provided settings (ID1), such as:“Many functions are very difficult to find, for example which information can be seen by my friends or everybody” and“The way how you can control the access to your personal information is described too difficult”.Others complain about both missing functions over the control of published information (ID2) and over other users (ID3): “Because you can’t delete everything at once, you have to click through every single interaction you’ve made”;“Always the one setting I’m searching for does not exist”;“I wish to protect my profile even more from non-friends and unknown people”;“Because there are situations, when friends of you saw some of your activities on Facebook, of which you thought that even them aren’t able to see”;“There are still too many possibilities for non-friends to acquire information about me with-out my knowledge”; and “Because I have no control about what others do with my data”. Moreover, respondents of both nationalities stated concerns about the changing nature of Facebook (ID4), especially regarding its terms and condition clauses: “They can change the terms and conditions or other stuff without letting me know” and “A change in […] terms and conditions may reveal previously hidden information without the knowledge of the user” Solely German respondents state concerns in the open-ended question over the inability to delete the user account and user data permanently (ID5): Studies show that data isn’t ever completely deleted and « can » turn up in the strangest places”; “Because your account can’t be deleted”; and “We as users should have the possibility to control, which information Facebook will have forever and which not, because even when I delete something from my wall, Facebook still has my information”. Besides, users state concerns about what Facebook Inc. and its partners do with personal information (ID6): “There was a case about Facebook posting private messages from 2009 or 2010 on the time-line of the users”; “My information could be given to anyone without me knowing”; “I do not know how much information and which information Facebook keeps about me and what Facebook uses them for”; and “Very unclear and little information about how & which channels various companies can access/view your personal info”. These findings match the survey results according to which German and Swedish respond-ents feel uncomfortable with the provided control over third parties collecting provided in-formation. In fact, nearly every third German and Swedish respondent is concerned about the information usage of either Facebook Inc. or its partners How the cultural differences in the user perception of Facebook’s provided privacy control affect the actual usage of existing settings and how both nationalities differ in this regard, remains to be seen in the following section.

1 Introduction

1.1 Problem

1.2 Purpose and Research question

1.3 Delimitations

1.4 Structure

1.5 Definitions

2 Theoretical Framework

2.1 Social Networks and Social Networking Sites

2.2 Privacy and Privacy on SNSs

2.3 Privacy in Facebook

2.4 Cultural Differences and Classification of Culture

3 Methods

3.1 Research Design

3.2 Research Method

3.3 Sampling

3.4 Confidence

3.5 Analysis Methods

3.6 Survey Instrument and Reliability

4 Results

4.1 Friends and Relationships on SNSs

4.2 Trust and Confidence on SNSs

4.3 Privacy Concerns

4.4 Self-Disclosure on SNSs

4.5 Control over Personal Information on SNSs

5 Analysis

5.1 Friends and Relationships on SNSs

5.2 Trust and Confidence on SNSs

5.3 Privacy Concerns

5.4 Self-Disclosure on SNSs

5.5 Control over Personal Information on SNSs

6 Discussion

6.1 Discussion of Results

6.2 Discussion of Methods

6.3 Implication for Research

6.4 Implication for Practice

6.5 Future Research

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

Cultural Differences in User Privacy Behavior on Social Networking Sites