Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

Introduction

Research methodology has been defined by a number of authors including Babbie and Mouton 2001; Cohen, Manion and Morrison 2000:44; Creswell and Clark 2007; Flick 2006; Kothari 2004:5; O’Leary 2004:9. O’Leary (2004:1) looked at research as an open-ended process that is likely to generate as many questions as it does answers. According to Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2000:45), social science researches are activities and undertakings aimed at developing a science of behavior; the word science itself implies both normative and interpretive perspectives. Babbie and Mouton (2001:45) believed that social science is the systematic and scholarly application of the principles of a science of behavior to the problems of people within the social contexts.

O’Leary (2004:85) defined the word methodology as a framework associated with a particular set of paradigmatic assumptions used to conduct research. According to Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2000:44), if methods refer to techniques and procedures used in the process of data gathering, then the aim of methodology is to help us understand, in the broadest possible terms, not the products of scientific inquiry, but the process itself.

The selection of methods and their application are always dependent on the aims and objectives of the study, the nature of the phenomenon being investigated and the underlying theory or expectations of the investigator (Babbie & Mouton 2001:48). According to O’Leary (2004:9), there is no best type of research. There are only good questions matched with appropriate procedures of inquiry.

This chapter presents the theoretical perspective of the study, research methodology and research design of the study.

Theoretical perspective of the study

This section provides the worldviews or paradigms that relate to mixed method research. The elements of quantitative and qualitative research methods, which provide a foundation for collecting and analyzing both forms of data in a mixed method study, are presented.

Quantitative and qualitative research paradigms

Positivism, constructivism and pragmatism are three research philosophies that have evolved over the century. The positivist philosophers, according to Johnson and Onwegbuzie (2004:14), are:

Quantitative purists who believe that social observations should be treated as entities in much the same way that physical scientists treat physical phenomena? Further, they contend that the observer is separate from the entities that are subject to observation.

According to O’Leary (2004:5), positivists believe that the world is a fixed entity whose mysteries are not beyond human comprehension. Their findings are always quantitative, statistically significant and generalizable. Positivists believe in empiricism, the idea that observation and measurement are at the core of the scientific endeavor (Henning 2004:17).

Positivists frameworks usually make excessive assumptions and claims are made to validity and accuracy of scientific knowledge. This paradigm does not take into consideration how people make meaning or how culture influences interpretation (Henning 2004:17). According to Cohen, Manion & Morrison (2000:1), positivism provides the clearest possible ideal of knowledge.

Post-positivists believe that the world may not be knowable. They see the world as infinitely complex and open to interpretation. They see the world as ambiguous, variable and multiple in realities. These findings are always inductive, dependable and auditable (Cameron 2009:140; O’Leary 2004:7).

Post-positivism research makes claim on the following:

Determination-cause-effect thinking;

Reductionism, narrowing and focusing on select variables to interrelate; and

Detailed observations and measures to interrelate theories that are continually refined (Creswell & Clark 2007:22).

Qualitative purists, also called constructivists, and interpretivists reject what they call positivisim. These purists contend that multiple-constructed realities abound, that time and context-free generalizations are neither desirable nor possible. That research is value bound, that it is impossible to differentiate fully causes and effects, that logic flows from specific to general and that the knower and known cannot be separated because the subjective knower is the only source of reality (Cameron 2009:140; Cherryholmes 1992:13; Ngulube, Mokwato & Ndwandwe 2009:106). In constructivist approaches, the inquirer works from the bottom up using the participant’s view to build broader themes and generate a theory interconnecting themes (Creswell & Plano Clark 2007:22).

The distinction between the qualitative and quantitative paradigms lies in the quest for understanding and in-depth inquiry. In quantitative study, the focus is on controlling all components in the actions and representatives of the participants. Respondents or research subjects are usually not free to express data that cannot be captured by predetermined instruments. In qualitative study, the variables are usually not controlled because it is exactly this freedom and natural development of action and representation that we wish to capture. Qualitative studies usually aim for depth rather than quantity of understanding. The distinction between the qualitative and quantitative paradigms lies between the quest for understanding and in-depth inquiry (Babbie & Mouton 2001:309; Flick 2006:33; Henning 2004:3; O’Leary 2004:99).

According to O’Leary (2004:99), quantitative and qualitative approaches have come to represent a whole set of assumptions that dichotomize the world of methods and limits the potential of researchers to build their methodological designs from their questions. In direct opposition to the ‘purists’ are the pragmatists who argue against a false dichotomy between the qualitative and quantitative research paradigms and advocate for efficient use of both approaches (Cameron 2009:140; Creswell 2003:4; Fielzer 2010:6).

Mixed Method Research Paradigm

Primarily the pragmatists advocated the third research paradigm, namely mixed method research. Mixed method research is based on the pragmatism philosophy (Cameron 2004:141; Flick 2006:33; Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner 2007:112; Ngulube, Mokwatlo & Ndwandwe 2009:106). Mixed methods research uses a method and a philosophy that attempt to fit together the insights provided by qualitative and quantitative research into a workable solution (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie 2004:16).

Cherryholmes (1992:13) explains that Charles Sanders Peirce’s statement in 1905 was the first declaration of pragmatism. The statement reads as follows:

The word pragmatism was invented to express a certain maxim of logic. The maxim is intended to furnish a method for the analysis of concepts. The method prescribed in the maxim is to trace out in the imagination the conceivable practical consequences – that is, the consequences for deliberate, self-controlled conduct of the affirmation or denial of the concept.

Cherryholmes (1992:13) further elaborates that William James and John Dewey shifted attention to the importance of the consequences of actions based upon particular conceptions. Dewey wrote: “Pragmatism does not insist upon consequent phenomena nor upon the precedents, but upon possibilities of action” (Cherryholmes 1992:13). Baert (2005:194) reiterates that:

Cognitive aims of social investigation include the critique of society (which ties in with self-emancipation or the lifting of past restrictions), understanding (which comes down to the attribution of meanings to texts or practices).

Pragmatism offers an epistemological justification (that is via pragmatic epistemic values or standards) and logic (that is, it uses the combination of methods and ideas that helps one best frame, address, and provide tentative answers to one’s research questions for mixing the approaches (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner 2007:125). The pragmatist worldview focuses on the consequences of research, the primary importance of the question asked rather than the methods, and multiple methods of data collection that inform the problems under study. Thus it is pluralistic and oriented toward “what works” in practice (Creswell & Clark 2007:26; Feilzer 2010:8). According to Feilzer (2010:8), pragmatism allows the researcher to be free of mental and practical constraints imposed by the forced dichotomy between positivism and constructivism.

Fielzer (2010:14) noted: “pragmatism brushes aside the quantitative/qualitative divide and ends the paradigm war suggesting that the most important question is whether the researcher has helped to find out what the researcher wants to know”. This study was based on the research philosophy of pragmatism.

Mixed Method Research

According to Cameron (2009:141), mixed method research has been described as a “quiet revolution due to its focus of resolving tensions between the qualitative and quantitative methodological movements”. Mixed methods research is, generally speaking, an approach to knowledge (theory and practice) that attempts to consider multiple viewpoints, perspectives, positions, and standpoints (always including the standpoints of qualitative and quantitative research) (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner 2007:113).

The mixed method approach to research tends to base knowledge claims on pragmatic grounds (for example consequence-oriented problem-centered and pluralistic). It employs strategies of inquiry that involve collecting data either simultaneously or sequentially to best understand research problems. The data collection also involves gathering both numeric information (for example on instruments) as well as textual information (for example, through interviews) so that the final database represents both quantitative and qualitative information (Creswell 2003:19; Johnson & Onwuegbuzie 2004:14).

According to Onwuegbuzie et al (2009:129), pragmatist researchers can use the whole range of qualitative and quantitative (that is descriptive and inferential analytical techniques) analyses in an attempt to fulfill one or more of five mixed research purposes (triangulation, complementarities, developmental, initiation and expansion).

The principles of mixed methodology have been applied as an approach to examining and enhancing the quality of academic libraries in recent years. These include the methods of assessing service quality (Calvert and Hernon 1997; Melo and Sampaio 2007); e-library evaluations and outcome assessment (Dugan and Hernon 2002; Hernon 2002b); information control (Kayongo and Jones 2008); performance measurement (Poll and Boekhorst 1996); and self-evaluation (Stein et al, 2008).

Mixed methods research is the research that:

Partners with the philosophy of pragmatism in one of its forms (left, right, middle);

Follows the logic of mixed methods research (including the logic of the fundamental principle and any other useful logics imported from qualitative or quantitative research that are helpful for producing defensible and usable research findings);

Relies on qualitative and quantitative viewpoints, data collection, analysis and inference techniques combined, according to the logic of mixed methods research, to address one’s research questions; and

Is cognizant, appreciative, and inclusive of local and broader socio-political realities, resources and needs (Johnson, Onwuegbuzie & Turner 2007:129).

In formulating the theoretical perspective of studying the impact of external quality assurance on academic libraries in Kenya, the mixed method research approach provides a useful prototype. The reasons for applying the mixed method methodology have been explained in sections 3.1.1, 3.1.2 and 3.1.3 of this chapter. In summary as stated by Ngulube, Mokwatlo and Ndwandwe (2009:109) the use of mixed research methods offers an opportunity for researchers to counterbalance the biases, limitations and weaknesses of either the qualitative or quantitative research approaches. The application of different approaches of mixed methods for this study was presented in the subsequent sections.

Research Design

The ultimate goal of social science research is to produce an accumulating body of reliable knowledge. Such knowledge enables us to explain, predict and understand empirical phenomena that interest us. Research design is governed by the notion of ‘fitness for purpose’ (Babbie & Mouton 2001:79; Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2000:73).

A research design is a blue-print of how the research will be conducted (Babbie & Mouton 2001:74). According to Creswell and Clark (2007:5), research design refers to the plan of action that links the philosophical assumptions to specific methods and techniques of data collection and analysis. Research design focuses on the end product, that is, what kind of study is being planned and what kinds of results are aimed at and the research problem. Research methodology focuses on the research process and the kind of tools and procedures to be used (Babbie & Mouton 2001:75). Methods are the techniques used in research to gather data, which is used as a basis for inference and interpretation, for explanation and prediction (Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2000:44-45). Methods are the techniques used to collect data, that is interviewing, surveying, participative observation. Tools are the devices used that facilitate the collection of data. They include questionnaires, observation checklists and interview schedules and methodological design is the plan for conducting your study which includes all the above. The number one prerequisite is that the designs address the research questions (O’Leary 2004:85).

Mixed Method Research Design

Mixed method research designs use both the quantitative and qualitative approaches in a single research project to gather or analyze data (Cameron 2009:143). Creswell and Plano Clark (2007:59) used the term mixed method design and suggested four major types of mixed method design such as triangulation, embedded, explanatory and the exploratory design.

However according to Creswell (2009:103) there has been much development in the area of mixed methods research designs and the author has learned that:

Designs used in practice are much more subtle and nuanced than I had first imagined. We now know that these designs are not complex enough to mirror actual practice, although I would argue that they are well suited to researchers initiating their first mixed methods study.

Creswell (2009:104) further suggests that mixed method design should be looked at, not as designs, but as a set of interactive parts. The author further states that instead of looking at mixed methods as a priority of one approach over the other or a weighting of one approach, the researcher should consider the equal value and representations of each. Ngulube, Mokwatlo and Ndwandwe (2009:107) added that mixed method research should focuses on fusing together qualitative and quantitative approaches and intertwining them. The mixing can occur at any stage of the research.

Cameron (2009:145) differentiates between mixed method design and mixed model design. Mixed method design is defined as the mixing of the quantitative and qualitative approaches only in the methods stage of a study. Mixed model designs involve the mixing of the quantitative and qualitative approaches during several stages of a study. However, Tashakkori (2009:289) explains further that mixed methods study must have two types of data that is qualitative and quantitative. It must also have a mixed question, two types of analysis (that might include the conversion of one type of data to another) and integrated inferences.

Meanwhile according to Creswell (2009:104), the designs have begun to incorporate unusual blends of methods, such as combinations of quantitative and qualitative longitudinal data, discourse analysis and survey data, secondary datasets and qualitative follow-ups, and joint matrices of quantitative and qualitative data in the same table. However, Creswell and Tashakkori (2007: 306) pointed out that:

In a sequential mixed method design, a researcher may begin with a quantitative survey (embracing a post-positivist perspective) to answer a theory-driven research question and move to collecting qualitative focus group data (embracing a constructive perspective) in response to a qualitative question.

In addition, Onwuegbuzie, Bustamante and Nelson (2010:63) suggested:

The development of a quantitative instrument traditionally considered an activity that belongs to the post-positivist philosophical stance could involve both quantitative and qualitative analyses.

At the research design stage, quantitative data can assist the qualitative component by identifying representative sample members, as well as outlying (that is deviant) cases. Conversely, at the design stage, qualitative data can assist the quantitative component of a study by helping with conceptual and instrument development. At the data collection stage, quantitative data can play a role in providing baseline information and helping to avoid “elite bias” (Johnson, Onwegbuzie & Turner 2007:115).

Tashakkori (2009:288) states that scholars of mixed methods studies seem to agree on a variety of other conceptual and methodological studies including:

The importance of identifying a sequence of (qualitative and quantitative) strands/phases (for example, sequential, parallel, or conversion process of data collection and analysis) and;

Explicitly identifying what type of data collection procedures or type of data is needed (for example, observation and self-report questionnaires) for answering the (mixed) research questions.

Mixed Method Research Typologies

In the literature on mixed method, various research typologies have been suggested by authors including Cameron (2009:142); Collins and O’Cathain (2009:3); Creswell (2009:101); Creswell and Clark (2007:58); Feilzer (2010:6); Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004:19); Ngulube, Mokwatlo & Nwandwe (2009:107); Nigas (2009:2); Onwuegbuzie et al: (2007:5); and Onwuegbuzie, Bustamente and Nelson (2010:57) .

Cameron (2009:143-145) discussed the typologies of mixed method designs, these included designs by:

Caracelli’s and Greene’s (1997) typology which included three component designs (triangulation, complementary and expansion) and four integrated designs (iterative, embedded/nested, holistic and transformative);

Tashakkori’s and Teddlie’s (2003) had six types of multi-strand – mixed method and mixed model study-with procedures that are concurrent, sequential and conversion; and Creswell’s and Clark’s (2007) had four types of designs (triangulation, embedded, explanatory and exploratory).

Collins and O’Cathain (2009:3) caution novice researchers to be aware that: Typologies do not offer a panacea. The authors further advise researchers that in some cases typologies delineate only minimally the information required by the researcher, or give inconsistent information required by the researcher, or present overly complex information.

Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004:19) asked whether equal status should be given to quantitative and qualitative approaches or whether give one paradigm should be given the dominant status. Tashakkori (2010:289) pointed out that:

Determining the dominance of one approach or another is not readily possible in the beginning or even during the course of study. It is only during the process of integration and/or making conclusions that one might be (if at all) able to “assign” greater weight to the qualitative or quantitative components. The amount of data, size of sample or even time spent in the field collecting data do not necessarily translate to priority/dominance of one or another approach.

During reviews of the literature on mixed method designs, parallels have been noted between the typologies discussed by Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004), Cameron (2009) and Creswell and Clark (2007). Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004:19) developed two mixed method research typologies, that is mixed model designs and mixed method designs. The mixed model designs are constructed by mixing qualitative and quantitative approaches within and across the stages of research. Mixed method design is based on crossing of paradigm emphasis and time ordering of the quantitative and qualitative phases. The authors also suggested that:

One can easily create more specific and more complex designs, for example, one can develop a mixed method design that has more stages; one can also design a study that includes both a mixed model design and a mixed method design features (Johnson & Onwuegbuzie 2004:19).

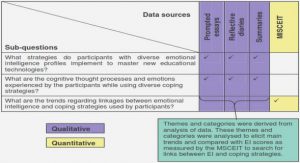

This study adopted a sequential mixed model design because more than one methodology was used and data was collected in two phases. The sequential mixed model design applied in this study was based on the typology of the mixed model design discussed by Johnson and Onwuegbuzie (2004:19). Thus, the aims, objectives and the research questions in this study were achieved by doing a literature review, using documentary sources, questionnaires and interviews to generate both qualitative and quantitative data.

Data Collection

Various authors including Babbie and Mouton (2001:230), Cohen, Manion and Morrison (2000:169), O’Leary (2004:153), Nachmias and Nachmias (1992:216), Patton (1990:14), and Sapsford (2007:6), have mentioned surveys as a common method used to collect data in social science research.

O’Leary (2004:152) defined survey as “information gathered by asking a range of individuals the same questions related to their characteristics, attributes, how they live or their opinions”. Meanwhile, Sapsford (2007:12) defined survey as a research style that involves systematic observation or systematic interviewing to describe a natural population and generally draw inferences about causation or patterns of influence from systematic covariation in the resulting data.

The advantages of self-completed questionnaires over structured interviews are that they are cheap to administer, they save time and the questions are standardized. The disadvantage of questionnaires over the interview survey is that there is no one to explain to the respondents the questions (Babbie & Mouton 2001:230; Cohen, Manion & Morrison 2000:117; Sapsford 2007:110).

One of the most important factors that contribute to the popularity of surveys relates to the advances in computer technology, which have also made analysis of large sets of data possible (Babbie & Mouton 2001:231). However, survey research is weak in validity and strong on reliability. In comparison with field research, for example, the artificiality of the survey format puts a strain on validity by representing all subjects with a standardized stimulus. Nevertheless, survey research goes a long way toward eliminating unreliability in observations made by the researcher (Babbie & Mouton 2001:264).

Questionnaires and interview survey methods were used to collect both quantitative and qualitative data for this study. The advantages of either method were used to complement the disadvantages of the other in this study. Data was collected in two phases. This is mainly because they are the best methods available to the social scientist interested in collecting original data for describing a population that is too large to observe directly. They are also excellent vehicles for measuring attitudes and orientation in a large population (Creswell & Clark 2007:6; Babbie & Mouton 2001:232).

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Declaration

SUMMARY

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

DEDICATION

LIST OF TABLES

LIST OF FIGURES

LIST OF CHARTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS

CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION

1.0 Introduction

1.1 Background to the statement of the problem

1.2 Research Problem

1.3 Justification and originality of the study

1.4 Methodology

1.5 Limitations of the study and key assumptions

1.6 Ethical considerations

1.7 Outline of the thesis

1.8 Referencing conventions used in the study

1.9 Summary

CHAPTER TWO: REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

2.0 Introduction

2.1 Purpose of literature review

2.2 Accreditation: A process of external quality assurance

2.3. Performance measurement and indicators

2.4. Impact assessment in university libraries

2.5 Culture of assessment in academic libraries

2.6 Conceptual framework

2.7 Summary

CHAPTER 3: RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

3.0 Introduction

3.1 Theoretical perspective of the study

3.2 Research Design

3.3 Data Collection

3.4 Ethical considerations

3.5 Evaluation of the research methodology

3.6 Summary

CHAPTER FOUR: PRESENTATION OF FINDINGS

4.0 Introduction

4.1 Background Information of Respondents and University Libraries in Kenya

4.2 Accreditation, a process of external quality assurance

4.3 University Library Standards

4.4 Performance Measurements in Kenyan University Libraries

4.5 The Attitude of respondents towards performance measurement

4.6 Use of Performance indicators in Kenyan university libraries

4.7 Spearman’s Rank (Spearman’s Rho’) Coefficient Correlation Test of Significance

4.8 Summary

CHAPTER FIVE: INTERPRETATION AND DISCUSSION OF THE FINDINGS

5.0 Introduction

5.1 Background information

5.2. Awareness about the concept of accreditation

5.3 Attitude towards the CHE Standards used during the accreditation process

5.4 Data collected in university libraries as measures of quality

5.5 Attitude on performance measurement

5.6 Usage of performance criteria and indicators

5.7 Summary of the chapter

CHAPTER SIX: SUMMARY CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

6.0 Introduction

6.1 Summary of the study

6.2 Conclusions

6.3 Conclusions on the statement of the problem

6.4 Recommendations

6.5 Implications for policy and practices in the assessment of university libraries

6.6 Suggestions for further research

BIBLIOGRAPY

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT