Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Chapter III The End of VPI as the Center of the Veterinary Complex

The dispersal of Virginia s veterinary complex at VPI may well be traced back to the mushrooming growth of the complex and demands of the components activities. There were increasing veterinary classes offered at VPI, more diseases to research, more information to share with livestock owners, and more regulatory demands placed on the State Veterinarian.

This increase in veterinary activities at VPI contributed greatly to the eventual fragmentation of the complex. The decrease of the dissemination of veterinary knowledge to farmer had a lot to do with the professionalization of veterinary medicine throughout the state and the nation.

Nevertheless, the clearest indication of the beginning of the fragmentation is found in a letter from James Ferneyhough to McBryde, VPI’s President. Employed in 1902 as both an associate faculty member in the VPI Veterinary Science Department and State Veterinarian,186 Ferneyhough confided the following about his appointment as State Veterinarian: “I do not want the appointment unless you think I am competent to fill the place nor do I want to be an applicant for the Chair if you think that Dr. John Spencer [head of VPI s Veterinary Science Department between 1902 and 1908] is the man for that position.”187 The letter clearly indicates that Ferneyhough felt unsure of his professional abilities, even though he had the desire to serve. As the letter goes on to say, “I should be proud to be appointed Veterinarian of my state, if those who know me personally and know my credentials think that I am the man for the place.”188

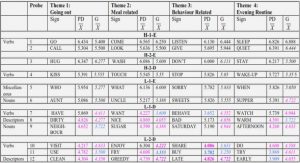

While Ferneyhough s hiring at VPI in 1902 marks the beginning of the fragmentation of the veterinary complex, the tenure of W. G. Chrisman, chair of VPI’s Veterinary Science Department between 1913 and 1923, marks its completion. The period between 1902 and 1913 was the turning point in the organizational structure of the veterinary complex. Spencer, the chair of VPI’s Veterinary Science Department between 1902 and 1909, and Ferneyhough performed different component tasks in Blacksburg between 1902 and 1908, then Chrisman and Ferneyhough served different component tasks–Chrisman in Blacksburg and Ferneyhough in Burkeville and Richmond–between 1913 and 1923 (see appendix 2). In 1913, Chrisman, a 1901 VPI graduate, became the head of the veterinary science department, while Ferneyhough continued his tenure as State Veterinarian. There seems to have been no designated veterinary researcher at VAES. Between 1913 and 1923, VAES had neither a veterinarian nor an animal pathologist on staff, and there is no documentation indicating a reason behind this vacancy.189 This fragmentation of the complex at VPI had a lot to do with the rapid growth of veterinary medicine and the specialization of the field within the United States. From the 1890s to the 1920s, veterinary medical researchers, including those from VPI, developed treatments and preventable measures for some of the most devastating domestic animal diseases, such as anthrax, cattle-tick fever, and diphtheria. These advances promoted disciplinary specialization and a professional division of labor. Accordingly, some veterinarians remained in private practice and contracted out their services involving control of outbreaks; others were employed by the BAI as inspectors of meat and dairy products intended for human consumption (with the objective of preventing disease from entering the human population).190 The BAI also employed veterinarians to determine if the livestock was free of contagious diseases, and thus allowed to pass quarantine borderlines.

Although the veterinary medical profession was specializing, many veterinarians feared that their profession would not survive into the next century. While professionalizing helped shape the identity of veterinarians, it also created strife between veterinarians and practitioners– such as uneducated horse doctors, agricultural agents, and livestock owners acting on their own or with the help of the Federal and State governments in efforts to combat livestock disease. The veterinary field was undergoing transformation for other reasons as well. For example, the introduction of the automobile limited the need for horses. Fewer horses to treat meant a smaller need for veterinarians focusing on horses. So, veterinary medicine had to reinvent itself as a caretaker of all animals in order to survive.191 With the loss of their equine clientele and other agents that treated and vaccinated livestock, veterinarians pushed to strengthen their profession by lobbying state and national legislators to restrict who could practice veterinary medicine. In Virginia, the VVMA voiced objections to extension agents practicing veterinary medicine. These professional concerns aside, the growing numbers of veterinarians still fell short of the numbers needed to address the needs of domesticated animals and public health in the early 1920s. This professional pressure eventually affected veterinary activities at VPI with the termination of VPI’s first Veterinary Science Department and the moving of veterinary related-courses to the Department of Zoology and Animal Pathology in 1925.

The first component of the veterinary complex to leave VPI grounds was the Office of State Veterinarian. The removal of this office, in about 1908, marked the beginning of the actual physical break up of the complex. Ferneyhough was State Veterinarian at this point and advocated that his office continue to remain connected with VPI.192 So, even though Ferneyhough’s physical office was located in 1910 in Burkeville away from the VPI Campus, the State Veterinarian still functioned under the auspices of the Virginia State Live Stock Sanitary Board (VSLSSB) on which Eggleston, president of VPI, served as ex-officio.193 In 1918, with Eggleston still on the VSLSSB, the State Veterinarian office was again re-located, this time to the Lyric Building in Richmond VA.194 Although the Office of State Veterinarian was neither physically connected with VPI nor under the aegis of the Board of Control of VAES, it remained connected with VPI via its president until at least 1920.

The dispersal of the veterinary complex from VPI also was manifested in a decline in veterinary research. By 1913, when Professor Chrisman joined VPI, veterinary research at VAES had decreased to the point that there had been no publications of veterinary research or veterinary-related bulletins between 1910 and 1923. The VAES Annual report of 1917-1918 lists no employed veterinarians or animal pathologists.195 A directory of all the administration and professional research staff of VAES between 1889 and 1965 mentions no veterinarian or animal pathologist employed between 1912 and 1924.196

In the years following 1913, the curriculum for veterinary education, the original component of the veterinary complex, underwent change. During I. D. Wilson’s first year at VPI in 1923, the veterinary science department had many of the same courses and administrative structures as it did during E. P. Niles’ tenure. During Wilson’s tenure (1923 -1959), the veterinary courses moved to the Zoology and Animal Pathology Department (in 1925). The shift reflected a change in the target audience for veterinary courses from agricultural students to students preparing for veterinary colleges. On the whole these changes created uncertainty about the future of the veterinary curriculum at VPI.

Some of the changes in the VPI veterinary curriculum were probably due to internal and external pressures on the college. Internally, the diversification of university course curricula contributed to the constant reshuffling of veterinary courses. Externally, the changing entrance requirements for veterinary medical colleges, coupled with the professional licensing constraints on who could practice veterinary medicine, affected the veterinary offerings of VPI. By the 1930s, many of the course and clinical experience requirements from the years 1891-1924 had disappeared or been incorporated into curricula unrelated to veterinary science, medicine, animal husbandry, or dairy husbandry. So, although veterinary science and medicine courses remained in the college curricula, they no longer enjoyed the same importance on the VPI campus as they had in the first thirty years or so under VPI’s Veterinary Science Department.

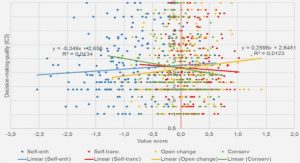

Comparing the network illustrating the complex in 1896 with that illustrating the same in the 1920s helps us visualize the changing composition of Virginia s veterinary complex (Figures 6 & 14). By 1910, the VPI campus did not dominate the Virginia State-controlled complex even as the office of State Veterinarian retained an external connection with VPI through President Eggleston’s presence on the VLSSB. All veterinary-related research bulletins at VAES stopped in 1910 with one last pre-1930 bulletin. Accordingly, in 1929, R. A. Runnells, a VAES staff veterinarian, authored a veterinary-bulletin entitled Baccillary White Diarrhea, Pullorum Infection of the Domestic Fowl, twenty-eight years after Mayo wrote Treatment of Bovine Tuberculosis in 1910 (see appendix 1).197 The only component of the veterinary complex that remained at VPI after 1910 was education. Since its inception in 1872, VPI has provided veterinary education by incorporating veterinary science and medicine into other courses, offering stand-alone veterinary courses, or much later, in 1980, by establishing a veterinary medical college. While Virginia s veterinary complex began dispersing across the state from 1910 onwards, its educational component remained on the VPI campus.

The 1896 complex shows a greater intermingling and connection of actors and components, allowing faculty to engage in many of the components’ activities. Twenty to thirty years later, in the 1920s, the complex is drastically different. In the 1920s complex actors and components were less interconnected because some of them, such as the State Veterinarian, moved off campus. The VAES no longer was a component in the1920s; however, veterinary education continued on the VPI campus.

Virginia Veterinary Medical Association’s (VVMA) Professionalization Efforts

From its beginnings in 1894, VVMA’s members insisted that the association’s mission consist of professionalizing veterinary medicine. They lobbied Virginia’s governors and state representatives to pass legislation that would govern the veterinary profession. The push to professionalize veterinary medicine gained strength between the 1910s and the 1930s, and conflicted with the incorporation of veterinary medicine into the agricultural curriculum of VPI during the McBryde administration (1891 – 1908). Before the 1920s, owing to the shortage of trained veterinarians, individuals with minimal training could diagnose, treat, and prevent disease in domestic animals. The small number of veterinarians hampered the efforts at professionalizing veterinary medicine; however this did not deter the association’s mission. Dr. Harbaugh, the first president of the VVMA (1896), pointed out:

It is almost incredible to think that this present association, with its present membership sprang from the handful of veterinarians who met in my office not quite two and a half years ago for the purpose of taking some steps to check the incursion of the quacks with diplomas. Vigorous attempts will certainly be made to have our Examining Board law repealed or amended, and we must be on the look out so as to be able to counteract every such attempt.198

The association was aware of politically uncertain standing, but it also realized that with time, growing membership, and effort it could add credibility to the veterinary profession. Throughout the 1920s and 1930s, VVMA was successful in strengthening the veterinary profession in Virginia.

Most of VVMA s success in professionalizing veterinary medicine came through supporting or resisting State legislative actions. VVMA supported passage of legislation in 1896 concerning the establishment of the Board of Veterinary Examiners, for which the VVMA submitted nominees to the governor.199 By suggesting names for another veterinary governing body, VVMA took its first step toward its goal of professionalizing veterinary medicine. In 1900, VVMA passed resolutions that publicly scorned state and municipal bodies that did not pass adequate disease control laws for livestock and animal products such as meat and milk.200 Because the association sought changes in the Veterinary Practice Act, VVMA monitored the Mills vs. Commonwealth case, which convened in Newport News, in 1908.201 Faville reports that the Newport News case dealt with an empiric practicing veterinary medicine and claiming to be a veterinarian. On this case, the judicial decision affected Virginia veterinary practice law, and it ruled that, based on the statute, anyone who practices on livestock without being a veterinarian can charge for his services and collect his bill, provided he does not claim to be a veterinary surgeon.202 Further, the decision claimed that the statute provided that no one who is not a veterinary surgeon has a right to prescribe for domestic animals, except those that are embraced in the term livestock.203 As the decision threw light on the legal implications of who could call themselves veterinarians and what they could do, the VVMA felt it had scored a point over non-veterinarians in violation of the state s veterinary law.

The VVMA attempted to be both the professional and political voice of Virginia s veterinarians as exemplified by a talk, “The Veterinarian as a Politician,” given in 1912 by Ferneyhough, then President of VVMA and State Veterinarian.204 In the talk, Ferneyhough advocated a closer relationship between the State Veterinarian and general practitioners.

Political interaction among veterinarians and other veterinary activities may have been one of the goals Ferneyhough and others in the VVMA hoped to achieve through their broader push for professionalism.205

The drive towards professionalism included VVMA s attempt at getting more involved in other veterinary activities in Virginia. So, in 1928, John R. Hutchinson, future president of VPI, spoke on “The Need for Well Trained Veterinarians in Virginia.” He stressed the need for cooperation among county agents and veterinarians, emphasizing that he did not want the county agents to practice veterinary medicine but rather to aid the veterinarians to meet the farmers’ needs.206 His statement appears to be a reaction to complaints from the VVMA about non-licensed county agents practicing veterinary medicine. This discontent of veterinarians over non-veterinarians providing basic services and advice to livestock owners and over the owners themselves practicing on their animals finally came to a head in 1938, when VVMA members could at last take action against such people.

In 1938, VVMA lobbied to kill an amendment to the Veterinary Practice Act. The amendment allowed county agents or their assistants or game wardens to administer vaccine to animals in counties in which there were no registered veterinarians.207 Despite VVMA s effort, this bill was approved by the Virginia Legislature, but Governor James H. Price vetoed the measure.208 With that veto, the VVMA can be said to have received state recognition at the highest level and to have been given full control over the conduct of the veterinary profession in Virginia. From 1938 on, only veterinarians could practice veterinary medicine in Virginia.

The professionalization of Virginia veterinary medicine necessitated changes in VPI’s veterinary curriculum. The increasing numbers and the political strengthening of Virginia’s licensed veterinarians resulted in a complete change in philosophy of veterinary education at VPI. No longer did it make sense to train agricultural students in veterinary medicine or to pass on veterinary knowledge directly to farmers. Through the 1910s and 1920s the veterinary profession had successfully forced the issue that only fully educated and trained veterinarians should be allowed to attend to the medical concerns of domestic animals. These medical concerns certainly dealt with diagnosing diseases, inspecting livestock for transport to slaughter, administering drugs, and medically treating diseases and ailments. However, non-veterinary practitioners such as farriers and livestock owners would help deliver offspring, shoe horses, dip livestock, and practice sanitary measures that would help ensure the good health of domestic animals. These non-veterinary medically-related activities are what VPI could teach their agricultural students after subsequent changes in Virginia s Veterinary Practice Act.

Preface

List of Illustrations

List of Abbreviations

Introduction

Chapter 1: The Emergence of The State of Virginia’s Veterinary Complex at VPI

The Age of the Horse Doctor: Veterinary Medicine in Virginia Prior to the 1890s

The Beginnings of Veterinary Medical Education at VPI

The Establishment of the Virginia Agricultural Experiment Station (VAES)

Dissemination of VAES Veterinary Research

The Establishment of the Office of State Veterinarian

The State of Virginia’s Veterinary Complex at VPI

Chapter 2: The State of Virginia’s Veterinary Complex at Work, 1896-1908

Veterinary Instruction at VPI, 1891-1924: Students, Faculty, and Curriculum

Veterinary Research, Bulletins, and Disease Outbreaks

The Role of the State Veterinarian

Veterinary Activities Outside Blacksburg

Chapter 3: The End of VPI as the Center of the Veterinary Complex

Virginia Veterinary Medical Association’s (VVMA) Professionalization Efforts

The State Veterinarian Moves Off Campus

Veterinary Education Down Scaled at VPI

The Veterinary Complex after the 1920s

Conclusion

Bibliography

GET THE COMPLETE PROJECT

Early Veterinary Activities at Virginia Polytechnic Institute, 1870s – 1920s: The Rise and Fall of Virginia’s State-Controlled Veterinary Complex