Get Complete Project Material File(s) Now! »

Assessing association of cement dust exposure with respiratory health

The assessment of association between cement dust exposure and respiratory health requires precise measurement. Furthermore, the strength of evidence is determined by the epidemiological study design used. Studies of exposure to environmental hazards generally have difficulties of precise measurements of exposure to the hazard.41 In the case of exposure to dust, and PM particularly, duration of exposure and the quantity an individual is being exposed to pose a great challenge to measurements. Additionally, variation in home/school ventilation, personal habits like smoking, meteorological effects like humidity and wind direction and wind speed could all affect the relationship between exposure and outcome.42-44 Precise measurement of the extent of an individual’s exposure to the environmental dust calls for personal monitoring and obtaining biological markers.45 Personal monitoring involves placing a measurement instrument, sampler, in the breathing zone of an individual. The samplers record time-integrated concentrations, reading concentrations directly or time integrated samplers that need laboratory analysis. Biological markers, which are more precise measurements and good for assessing doseresponse relationships, are measured by obtaining tissue samples from exposed individuals. However, these methods, though precise are usually not feasible for most settings; they are expensive, labour intensive, time-consuming and invasive, and involves study participants carrying the sampling equipment. In assessing exposure to cement dust and respiratory health, few studies have used personal monitoring in occupational setting studies.45-48 Other studies, especially those based on the community, have used less precise methods of quantifying exposure, the commonest being environmental monitoring.18,49 This entails placing monitoring devices at specified locations for periods ranging from 8 to 24 hours. This is a proxy measure of exposure for individuals being studied. It has been argued that subjects have been assigned concentrations measured at central region sites or outdoor sites indicating that this may lead to exposure misclassification and diminish the accuracy of exposure response estimates because many people spend most of their time indoor. Although, this may not be true for most communities in developing countries like Zambia where most people tend to spend most of their time outdoor because the houses are very small and are mostly used for sleeping.

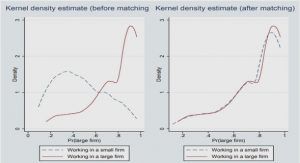

Regarding study designs, most of the studies in the current literature used a cross sectional study design in combination with the imprecise methods of measuring exposure.6,37,50 It is thus difficult to draw firm conclusion on association and/or causal relationships. Cross sectional studies are weak to prove causality because it is difficult to demonstrate temporality between exposure and outcome, a cardinal feature of the Bradford Hills criteria.51 cohort studies, on the other hand, provide stronger evidence when studying association of exposure and outcome. Panel studies which involve repeated measurements of both the exposure and the outcomes on the same individuals provide even more accurate estimate in the variation of respiratory effects due to the exposure.

Socio Economic Characteristics of the Communities

Although, the majority of houses in both communities were made of concrete material, Bauleni compared to Freedom, had a significantly higher proportion (p-value = 0.020) (Table 3-2). The majority of houses in Freedom were roofed with asbestos while metal sheets were used for most houses in Bauleni. A statistically significant higher proportion of houses in Freedom were plastered (p value = 0.010). No statistically significant differences in the distributions of number of rooms and windows were observed between the communities. Most houses in both communities had up to two rooms and up to three windows per structure with no statistically significant difference. Only a minority of houses owned a floor carpet in the two communities; with no statistical significant difference between communities (p value = 0.260).

While the source of energy for lighting was the same for both communities, energy source for cooking was statistically significantly different between the communities; majority of households in Freedom used charcoal as source of energy for cooking and had cooking areas located within the dwelling house.

Predictors of Mucous Membrane Irritations

Area of residence, time where respondents spent most of the time, location of the cooking area or kitchen and source of energy for cooking were significant predictors of eye irritation in bivariate analyses (Table 3-5). After adjusting for time where respondents spent most of the time, location of the kitchen and source of energy for cooking, respondents in Freedom were 2.50 (95% CI [1.65 – 3.79]) times more likely to have eye irritation than those in the control community. Respondents who spent time around their home were 1.8 times more likely to have eye irritations controlling for other factors. However, when stratified by area of residence there was evidence of effect modification; respondents from Freedom who spent time around home were 2.8 times more likely to experience eye irritations while respondents of Bauleni were only 1.7 times more likely to experience eye irritations.

In bivariate analyses, residence, age, gender, and source of energy for cooking were found as significant predictors for nose irritation. Although result not included in Table 3-5, duration of living in the community showed effect modification; living in Freedom community increased the odds of nose irritation by 1% (OR 1.01, p-value = 0.008) while it had no effect for respondent living in Bauleni (OR 1.00, p-value = 0.683). In multivariate models only residence, age and gender retained statistical significance. Compared to respondents from the control community, respondents from the exposed community were 4.36 (95% CI [2.96 – 6.55]) times more likely to have nose irritation.

Independent determinants of sinus irritations included area of residence, age, education, and occupational status, source of energy for cooking and presence of floor carpet (Table 3-5). However, only residence, age and occupation retained statistical significance after adjusting for the other predictors. Respondents from the exposed community were 1.94 (95% CI [1.19 – 3.18]) more likely to have sinus irritation compared to those from the control community adjusting for confounders. Duration of living in the exposed community showed no effect on risk of sinus irritations.

CHAPTER 1 : INTRODUCTION TO AIR POLLUTION AND RESPIRATORY HEALTH

1.1. BACKGROUND INFORMATION

1.2. AIR QUALITY STANDARDS

1.3. CEMENT PRODUCTION, PM AMBIENT AIR POLLUTION AND HEALTH EFFECTS

1.4. ASSESSING ASSOCIATION OF CEMENT DUST EXPOSURE WITH RESPIRATORY HEALTH

1.5. RESPIRATORY SYMPTOMS

1.6. EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIES ON CEMENT DUST AMBIENT POLLUTION AND HUMAN HEALTH

1.7. RESEARCH QUESTION

1.8. AIM

1.9. OBJECTIVES

1.10. STUDY HYPOTHESES

1.11. RELEVANCE OF THE STUDY

1.12. REFERENCES

CHAPTER 2 : RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

2.1. STUDY LOCATION AND STUDY POPULATION

2.2. SAMPLE SIZE DETERMINATION

2.3. SELECTION OF STUDY PARTICIPANTS

2.4. STUDY PROCEDURE

2.5. PERFORMANCE OF MEASUREMENTS

2.6. REFERENCE

CHAPTER 3 : PREVALENCE OF AND DETERMINANTS OF MUCOUS MEMBRANE IRRITATIONS IN A COMMUNITY NEAR A CEMENT FACTORY IN ZAMBIA: A CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY

3.1. ABSTRACT

3.2. INTRODUCTION

3.3. MATERIAL AND METHOD

3.4. RESULTS

3.5. DISCUSSION

3.6. CONCLUSION

3.7. ETHICAL CONSIDERATION

3.8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

3.9. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

3.10. CONFLICT OF INTEREST

3.11. REFERENCES

3.12. SUPPLEMENTARY FILE: SELECTION OF STUDY PARTICIPANTS

CHAPTER 4 : PREVALENCE OF SELF-REPORTED PULMONARY SYMPTOMS IN A COMMUNITY RESIDING NEAR A CEMENT FACTORY IN CHILANGA, ZAMBIA: A CROSS SECTIONAL STUDY

4.1. ABSTRACT

4.2. BACKGROUND

4.3. MATERIAL AND METHODS

4.4. RESULTS

4.5. DISCUSSION

4.6. CONCLUSION

4.7. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

4.8. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

4.9. ETHICAL CONSIDERATIONS

4.10. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

4.11. REFERENCES

CHAPTER 5 : EFFECTS OF AIRBORNE PARTICULATE MATTER ON RESPIRATORY HEALTH IN A COMMUNITY NEAR A CEMENT FACTORY IN CHILANGA, ZAMBIA: RESULTS FROM A PANEL STUDY

5.1. ABSTRACT

5.2. INTRODUCTION AND BACKGROUND

5.3. STUDY METHODOLOGY

5.4. RESULTS

5.5. DISCUSSION

5.6. CONCLUSIONS

5.7. ABBREVIATIONS

5.8. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

5.9. AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

5.10. CONFLICTS OF INTEREST:

5.11. REFERENCE

CHAPTER 6 : EXPOSURE TO CEMENT DUST AND RESPIRATORY HEALTH FOR COMMUNITIES RESIDING NEAR CEMENT FACTORIES: A SYSTEMATIC REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

6.1. ABSTRACT

6.2. INTRODUCTION

6.3. STUDY METHODOLOGY

6.4. RESULTS

6.5. DISCUSSION

6.6. CONCLUSION

CHAPTER 7 : CONCLUSION AND RECOMMENDATIONS

7.1. BACKGROUND

7.2. POTENTIAL BIAS, LIMITATIONS AND UNCERTAINTIES

7.3. STRENGTH OF THE STUDY

7.4. CONCLUSION, FUTURE PERSPECTIVES AND RECOMMENDATIONS

7.5. Policy and practice

7.6. Research

7.7. REFERENCE